Agency Activities: Air Quality (FY2017-2018)

The following summarizes the agency’s activities regarding criteria pollutant standards, requirements under various federal air quality standards, evaluating health effects, the Air Pollutant Watch List, shale oil and gas, environmental research and development, and major incentive programs. (Part of Chapter 2—Biennial Report to the 86th Legislature, FY2017-FY2018)

Air Quality

Changes to Standards for Criteria Pollutants

The federal Clean Air Act requires the EPA to review the standard for each criteria pollutant every five years to ensure that it achieves the required level of health and environmental protection. Federal clean-air standards, or the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), cover six air pollutants: ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. Attaining the ozone standards continue to be the biggest air quality challenge in Texas.

As the TCEQ develops plans—region by region—to address air quality issues, it revises the State Implementation Plan (SIP) and submits these revisions to the EPA.

Ozone Compliance Status

2008 Ozone Standard

On May 21, 2012, the EPA published final designations for the 2008 eight-hour ozone standard of 0.075 ppm. The Dallas–Fort Worth (DFW) area was designated “nonattainment,” with a “moderate” classification, and the Houston-Galveston-Brazoria (HGB) area was designated “nonattainment,” with a “marginal” classification. The attainment demonstration and reasonable further progress SIP revisions for the DFW 2008 eight-hour ozone nonattainment area were adopted in June 2015. An additional attainment demonstration to address a revised 2017 attainment year was adopted in July 2016.

The EPA approved the DFW reasonable further progress SIP revision in December 2016 and proposed approval of the attainment demonstration in May 2018. The DFW area was required to attain the 2008 eight-hour ozone standard by July 20, 2018, and the HGB area was required to do so by July 20, 2015. Both areas did not attain by the applicable dates. The EPA reclassified the HGB area to moderate nonattainment effective Dec. 14, 2016. The new attainment deadline was July 20, 2018, with a 2017 attainment year, which is the year that the area was required to measure attainment of the applicable standard. The attainment demonstration and reasonable further progress SIP revisions for the HGB 2008 eight-hour ozone moderate nonattainment area were adopted in December 2016. The EPA proposed approval of the HGB reasonable further progress SIP revision in April 2018 and of the attainment demonstration in May 2018.

Because both areas did not attain by the end of 2017, the EPA is expected to reclassify both the DFW and HGB 2008 ozone nonattainment areas to serious. The reclassifications are expected to be completed in early 2019. It is anticipated that the submission deadline for required serious area attainment demonstration and reasonable further progress SIP revisions will be approximately one year after the EPA’s final reclassification.

2015 Ozone Standard

In October 2015, the EPA finalized the 2015 eight-hour ozone standard of 0.070 parts per million. The EPA was expected to make final designations by Oct. 1, 2017, using design values from 2014 through 2016. On Nov. 16, 2017, the EPA designated a majority of Texas as attainment/unclassifiable for the 2015 eight-hour ozone NAAQS. The designations for four areas—DFW, HGB, El Paso, and San Antonio—remained pending.

On June 4, 2018, the EPA published final designations for the remaining areas, except for the eight counties that compose the San Antonio area. Consistent with state designation recommendations, the EPA finalized nonattainment designations for a nine-county DFW marginal nonattainment area (Collin, Dallas, Denton, Ellis, Johnson, Kaufman, Parker, Tarrant, and Wise counties) and a six-county HGB marginal nonattainment area (Brazoria, Chambers, Fort Bend, Galveston, Harris, and Montgomery counties). The EPA designated all the remaining counties, except those in the San Antonio area, as attainment/unclassifiable. The designations are effective Aug. 3, 2018.

On July 17, 2018, the EPA designated Bexar County as nonattainment, and the seven other San Antonio area counties—Atascosa, Bandera, Comal, Guadalupe, Kendall, Medina, and Wilson—as attainment/unclassifiable.

The attainment deadline for the DFW and HGB marginal nonattainment areas is Aug. 3, 2021, with a 2020 attainment year. The attainment deadline for the Bexar County marginal nonattainment area is Sept. 24, 2021, with a 2020 attainment year. An emissions inventory SIP revision will be due to the EPA two years following the effective date of nonattainment designations.

Table 3. Ozone-Compliance Status for the 2015 Eight-Hour Standard

| Area of Texas | 2015 Eight-Hour Ozone | Attainment Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Houston-Galveston-Brazoria (six-county area) | Marginal Nonattainment | Aug. 3, 2021 |

| Dallas–Fort Worth (nine-county area) | Marginal Nonattainment | Aug. 3, 2021 |

| San Antonio (Bexar County) | Marginal Nonattainment | Sept. 24, 2021 |

| All Other Texas Counties | Attainment | not applicable |

Note: The HGB 2015 ozone nonattainment area comprises the counties of Brazoria, Chambers, Fort Bend, Galveston, Harris, and Montgomery. The DFW 2015 ozone nonattainment area comprises the counties of Collin, Dallas, Denton, Ellis, Johnson, Kaufman, Parker, Tarrant, and Wise.

Redesignation for Revoked Ozone Standards

On Feb. 16, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit issued an opinion in the case South Coast Air Quality Management District v. EPA, 882 F.3d 1138 (D.C. Cir. 2018). The case was a challenge to the EPA’s final 2008 eight-hour ozone standard SIP requirements rule, which revoked the 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS as part of the implementation of the stricter 2008 eight-hour ozone NAAQS.

The court’s decision vacated parts of the EPA’s final 2008 eight-hour ozone standard SIP requirements rule, including the redesignation substitute, the removal of anti-backsliding requirements for areas designated nonattainment under the 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS, the waiving of requirements for transportation conformity for maintenance areas under the 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS, and the elimination of the requirement to submit a second 10-year maintenance plan. On April 23, 2018, the EPA filed a request for rehearing on the case, and is awaiting a decision by the court.

To date, the EPA has provided limited guidance to states regarding the effects of the ruling on transportation conformity for the 1997 and 2008 eight-hour ozone NAAQS, but no guidance regarding SIP planning obligations arising from the court’s initial ruling.

This ruling results in uncertainty for applicants seeking air quality permits and for transportation projects for which conformity analyses may be needed, in areas that were designated nonattainment under the revoked one-hour ozone NAAQS of 0.12 parts per million (ppm) or 124 parts per billion (ppb) and the revoked 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS of 0.08 ppm or 84 ppb. Major source thresholds, significance levels, and emission offset requirements for air quality permitting are determined by the designation and classification level that applies in a nonattainment area. Some areas in Texas were classified at more stringent classification levels under the revoked one-hour and 1997 ozone NAAQS than currently applicable for the 2008 ozone NAAQS.

If an area does not have a valid motor vehicle emission budget (MVEB) or cannot demonstrate conformity to an existing MVEB, any transportation project using federal dollars cannot proceed without a demonstration that the emissions are no greater than if the project were not completed. Four areas of Texas are potentially affected by the ruling. To address the potential impacts of the court’s ruling, the TCEQ has initiated planning for expedited submittal to the EPA of formal redesignation requests and maintenance plans for each area.

Houston-Galveston-Brazoria

The HGB area (Brazoria, Chambers, Fort Bend, Galveston, Harris, Liberty, Montgomery, and Waller counties) is classified as a severe nonattainment area for both the one-hour and 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS. Because the area has monitored design values meeting both ozone NAAQS, the TCEQ submitted, and the EPA approved, redesignation substitutes for the HGB area for both NAAQS.

Dallas–Fort Worth

The DFW one-hour ozone area (Collin, Dallas, Denton, and Tarrant counties) is classified as serious nonattainment. The DFW 1997 eight-hour ozone area (Collin, Dallas, Denton, Ellis, Johnson, Kaufman, Parker, Rockwall, and Tarrant counties) is classified as serious nonattainment. Because the area has monitored design values meeting both NAAQS, the TCEQ submitted, and the EPA approved, redesignation substitutes for the DFW area for both NAAQS.

Beaumont-Port Arthur

The BPA area (Hardin, Jefferson, and Orange counties) is classified as serious nonattainment for the one-hour ozone NAAQS. The area was redesignated by the EPA to attainment for the 1997 eight-hour ozone standard in 2010 after approval of the TCEQ’s formal redesignation request and maintenance plan for the area. The BPA area is affected by the ruling in two ways. First, the vacatur of waiver of transportation conformity for redesignated areas may reinstate those requirements for the area, requiring compliance with MVEBs that may be difficult for the area to meet. Second, the ruling would reinstate the requirement for a second 10-year maintenance plan for the BPA area under the 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS.

El Paso

The El Paso area (El Paso County) is classified as serious nonattainment for the one-hour ozone NAAQS. Though the area was never formally redesignated, the EPA lifted anti-backsliding requirements for the area that would normally only be lifted after formal redesignation. The court’s vacatur of removal of anti-backsliding requirements for areas designated nonattainment under the 1997 NAAQS may also apply to areas that were designated nonattainment under the one-hour ozone NAAQS.

2010 Sulfur Dioxide Standard

The EPA revised the sulfur dioxide (SO2) NAAQS in June 2010, adding a one-hour primary standard of 75 parts per billion. In July 2013, the EPA designated 29 areas in 16 states, which did not include Texas, in nonattainment of the 2010 standard. On March 3, 2015, a U.S. district court order set deadlines for the EPA to complete designations for the SO2 NAAQS. It required that the EPA designate by July 2, 2016, any areas monitoring violations or with the largest SO2 sources fitting specific criteria for SO2 emissions.

The EPA identified 12 sources in Texas meeting these criteria for Round 2 designations. The EPA designated Atascosa (San Miguel), Fort Bend (WA Parish), Goliad (Coleto Creek), Lamb (Tolk), Limestone (Limestone Station), McLennan (Sandy Creek), and Robertson (Twin Oaks) counties as unclassifiable/attainment and designated Potter County (Harrington) as unclassifiable, effective Sept. 12, 2016. Designations for the remaining four EPA-identified Texas power plants—Big Brown, Martin Lake, Monticello, and Sandow—were delayed and the EPA published a supplement to the Round 2 SO2 designations on Dec. 13, 2016. Effective Jan. 12, 2017, portions of Freestone and Anderson counties (Big Brown), portions of Rusk and Panola counties (Martin Lake), and a portion of Titus County (Monticello) were designated nonattainment. Milam County was designated unclassifiable.

Sources with more than 2,000 tons per year of SO2 emissions not designated in 2016 would be designated based on modeling data by December 2017 in Round 3 or monitoring data by December 2020 in Round 4. In accordance with the August 2015 Data Requirements Rule, Texas identified 24 sources with 2014 SO2 emissions of 2,000 tons per year or more, which included the 12 sources identified in Round 2. The TCEQ evaluated the Oklaunion facility in Wilbarger County through modeling submitted to the EPA, for designation in Round 3. The EPA completed Round 3 designations for the 2010 SO2 NAAQS, effective April 9, 2018, designating Wilbarger County as unclassifiable/attainment along with unclassifiable/attainment designations for 237 other Texas counties or portions of counties. The areas designated unclassifiable/attainment in Anderson, Panola, Rusk, and Freestone counties are the parts of those counties not previously designated nonattainment in Round 2. All remaining areas not designated in rounds 2 or 3 are to be designated in Round 4 by Dec. 31, 2020, including the following areas of Texas, currently being monitored: Jefferson, Hutchinson, Navarro, Bexar, Howard. Harrison, and Titus (remaining partial area) counties.

In October 2017, Luminant (Vistra Energy) filed notices with the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) stating its plans to retire the Monticello, Sandow, and Big Brown power generation plants. Late in 2017, Vistra received determinations from ERCOT that these retirements would not affect system reliability. The TCEQ voided permits for these three plants on March 30, 2018. Big Brown and Monticello were the primary SO2 emissions sources of the areas designated nonattainment in Anderson, Freestone, and Titus counties. The Martin Lake plant, in the nonattainment area in Rusk and Panola counties, continues to operate.

Evaluating Health Effects

TCEQ toxicologists meet their goals of identifying chemical hazards, evaluating potential exposures, assessing human health risks, and communicating risk to the general public and stakeholders in a variety of ways. Perhaps most notably, the TCEQ relies on health- and welfare-protective values developed by its toxicologists to ensure that both permitted and monitored airborne concentrations of pollutants stay below levels of concern. Final values for 316 pollutants have been derived so far. Texas has received compliments about these values from numerous federal agencies and academic institutions, and many other states and countries use the TCEQ’s toxicity values.

TCEQ toxicologists use the health- and welfare-protective values it derives for air monitoring—called air monitoring comparison values (AMCVs)—to evaluate the public-health risk of millions of measurements of air pollutant concentrations collected from the ambient air monitoring network throughout the year.

When necessary, the TCEQ also conducts health-effects research on particular chemicals with limited or conflicting information. In fiscal 2016 and 2017, specific work evaluating arsenic and ozone was completed. This work can inform the review and assessment of human-health risk of air, water, or soil samples collected during investigations and remediation, as well as aid in communicating health risk to the public.

Finally, toxicologists communicate risk and toxicology with state and federal legislators and their committees, the EPA, other government agencies, the press, and judges during legal proceedings. This often includes input on EPA rulemaking, including the NAAQS, through written comments, meetings, and scientific publications.

Air Pollutant Watch List

TCEQ toxicologists oversee the Air Pollutant Watch List activities that result when ambient pollutant concentrations exceed these protective levels. The TCEQ routinely reviews and conducts health-effects evaluations of ambient air monitoring data from across the state by comparing air toxic concentrations to their respective AMCVs or state standards. The TCEQ evaluates areas for inclusion on the Air Pollutant Watch List where monitored concentrations of air toxics are persistently measured above AMCVs or state standards.

The purpose of the watch list is to reduce air toxic concentrations below levels of concern by focusing TCEQ resources and heightening awareness for interested parties in areas of concern.

The TCEQ also uses the watch list to identify companies with the potential of contributing to elevated ambient air toxic concentrations and to then develop strategic actions to reduce emissions. An area’s inclusion on the watch list results in more stringent permitting, priority in investigations, and in some cases increased monitoring.

Four areas of the state are currently on the watch list, which is available at <www.tceq.texas.gov/toxicology/apwl>. The TCEQ continues to evaluate the current APWL areas to determine whether improvements in air quality have occurred. For example, the TCEQ conducted two mobile monitoring trips this biennium around existing APWL areas that lack stationary air monitors. The TCEQ has also identified areas in other parts of the state with monitoring data close or slightly above AMCVs, and worked proactively with nearby companies to reduce air toxic concentrations, obviating the need for listing these areas on the APWL.

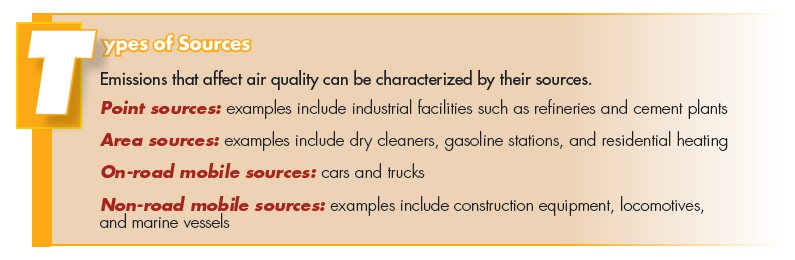

Oil and Gas: Boom of Shale Plays

The early activities associated with the Barnett Shale formation in the Dallas–Fort Worth area presented an unusual challenge for the TCEQ, considering that this was the first time that a significant number of natural gas production and storage facilities were built and operated in Texas within heavily populated areas. In response, the TCEQ initiated improved collection of emissions data from oil and gas production areas.

The TCEQ conducts in-depth measurements at all shale formations to evaluate the potential effects. The TCEQ continues to conduct surveys and investigations at oil and gas sites using optical gas imaging camera (OGIC) technology and other monitoring instruments.

The monitoring, on-site investigations, and enforcement activities in the shale areas also complement increased air-permitting activities. The additional field activities include additional stationary monitors, increased collections of ambient air canister samples, flyovers using OGIC imaging, targeted mobile monitoring, and investigations (routine and complaint-driven).

One vital aspect in responding to shale-play activities is the need for abundant and timely communications with all interested parties. The TCEQ has relied on community open houses, meetings with the public, county judges and other elected officials, workshops for local governments and industry, town-hall meetings, legislative briefings, and guidance documents. For example, the agency recently issued a new publication, Flaring at Oil and Natural Gas Production Sites (TCEQ GI-457). This brochure is designed to provide a helpful starting point for discussions with citizens; TCEQ staff can then provide more details as needed with each person. The agency also maintains a multimedia website, <www.TexasOilandGasHelp.org >, with links to rules, monitoring data, environmental complaint procedures, regulatory guidance, and frequently asked questions.

The TCEQ continues to evaluate its statewide network for air quality monitoring and will expand those operations when needed. Fifteen automatic-gas-chromatograph monitors operate in the Barnett Shale area, along with numerous other instruments that monitor for criteria pollutants. In addition, 16 VOC canister samplers (taking samples every sixth day) are located throughout TCEQ Region 3 (Abilene) and Region 4 (Dallas–Fort Worth).

In South Texas, the agency has established a precursor ozone monitoring station in Floresville (Wilson County), north of the Eagle Ford Shale; the station began operating on July 18, 2013. Another monitoring station has been established in Karnes City, which is in Karnes County; this station was activated on Dec. 17, 2014. Karnes County continues to lead the Eagle Ford Shale play in production and drilling activities. The data from these new monitoring stations is used to help determine whether the shale oil and gas play is contributing to ozone formation in the San Antonio area. It should be noted that existing statewide monitors located within oil and gas plays show no indications that these emissions are of sufficient concentration or duration to be harmful to residents.

Regional Haze

Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend national parks are Class I areas of Texas identified by the federal government for visibility protection, along with 154 other national parks and wilderness areas throughout the country. Regional Haze is a long-term air quality program requiring states to establish goals and strategies to reduce visibility-decreasing pollutants in the Class I areas and meet a “natural conditions” visibility goal by 2064. In Texas, the pollutants influencing visibility are primarily NOX, SO2, and PM. Regional Haze program requirements include an updated plan (Texas Regional Haze SIP revision) that is due to the EPA every 10 years and a progress report that is due to the EPA every five years, to demonstrate progress toward natural conditions.

The Texas Regional Haze SIP revision was submitted to the EPA on March 19, 2009. The plan projected that Texas Class I areas will not meet the 2064 “natural conditions” goal, due to emissions from the Ohio River Valley and international sources. On Jan. 5, 2016, the EPA finalized a partial disapproval of the 2009 SIP revision and proposed a federal implementation plan (FIP) effective Feb. 4, 2016. In July 2016, Texas and other petitioners, contending that the EPA acted outside its statutory authority, sought a stay pending review of the FIP; the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in favor of Texas and the other petitioners and stayed the FIP. The FIP would have required emissions control upgrades or emissions limits at eight coal-fired power plants in Texas. The EPA also approved the Texas Best Available Retrofit Technology (BART) rule for non-electric utility generating units, but due to continuing issues with the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, the EPA could not act on BART requirements for electric utility generating units (EGUs).

On Oct. 17, 2017, the EPA adopted a FIP to address BART for EGUs in Texas, which included an alternative trading program for SO2. The EPA will administer the trading program, which included only specific EGUs in Texas and no out-of-state trading. For NOX, Texas remains in CSAPR. For PM, the EPA determined no further action was required. On March 20, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit issued a ruling upholding “CSAPR-better-than-BART” for regional haze.

Texas’ first five-year progress report on regional haze was submitted to the EPA in March 2014. It contained:

- A summary of emissions reductions achieved from the plan.

- An assessment of visibility conditions and changes for each Class I area in Texas that Texas may have an impact on.

- An analysis of emissions reductions by pollutant.

- A review of Texas’ visibility-monitoring strategy and any necessary modifications.

On Jan. 10, 2017, the EPA published the final Regional Haze Rule Amendments to update aspects of the reasonably available visibility impairment (RAVI) and regional haze programs, including:

- Strengthening the federal land manager consultation requirements.

- Extending the RAVI requirements so that all states must address situations where a single source or small number of sources is affecting visibility at a Class I area.

- Extending the SIP submittal deadline for the second planning period from July 31, 2018, to July 31, 2021, to allow states to consider planning for other federal programs like the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, the 2010 one-hour SO2 NAAQS, and the 2012 annual PM2.5 NAAQS.

- Adjusting the interim progress report submission deadline so that second progress reports would be due by Jan. 31, 2025.

- Removing the requirement for progress reports to be SIP revisions.

In January 2018, the EPA announced it would revisit the 2017 amendment to the Regional Haze Rule, though no formal action has been taken regarding the rule.

Major Incentive Programs

The TCEQ implements several incentive programs aimed at reducing emissions, including the Texas Emissions Reduction Plan, the Texas Clean School Bus Program, and Drive a Clean Machine.

Texas Emissions Reduction Plan

The Texas Emission Reduction Plan (TERP) program gives financial incentives to owners and operators of heavy-duty vehicles and equipment for projects that will lower nitrogen oxides (NOX) emissions. Because NOX are a leading contributor to the formation of ground-level ozone, reducing these emissions is key to achieving compliance with the federal ozone standard. Incentive programs under TERP also support the increased use of alternative fuels for transportation in Texas, including fueling infrastructure.

- The Diesel Emissions Reduction Incentive (DERI) Program has been the core incentive program since the TERP was established in 2001. DERI incentives have focused largely on the ozone nonattainment areas of Dallas–Fort Worth and Houston-Galveston-Brazoria. Funding has also been awarded to projects in the Tyler-Longview-Marshall, San Antonio, Beaumont–Port Arthur, Austin, Corpus Christi, El Paso, and Victoria areas. From 2001 through August 2017, the DERI program awarded more than $1 billion for the upgrade or replacement of 19,001 heavy-duty vehicles, locomotives, marine vessels, and pieces of equipment. Over the life of these projects, 179,427 tons of NOX are projected to be reduced, which in 2018 equated to approximately 30 tons per day. The Emissions Reduction Incentive Grants Program, a program of the DERI, will be accepting applications through Aug. 15, 2018.

- The Texas Clean Fleet Program funds replacement of diesel vehicles with alternative-fuel or hybrid vehicles. From 2009 through August 2017, 28 grants funded 644 replacement vehicles for a total of $58.2 million. These projects included a range of alternative-fuel vehicles, including propane school buses, natural gas garbage trucks, hybrid delivery vehicles and garbage trucks, and electric vehicles. These projects are projected to reduce NOX by 660 tons of over the life of the projects. The next Texas Clean Fleet Program grant round is expected to open in August 2018.

- The Clean Transportation Triangle Program (CTTP) and the Alternative Fueling Facilities Program (AFFP) were combined under the AFFP by the Legislature in fiscal 2017 to provide grants to ensure that alternative-fuel vehicles have access to fuel and to build the foundation for a self-sustaining market for alternative fuels in Texas. The programs previously aimed at fueling stations along the interstate highways connecting the Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, and San Antonio areas, the counties within the triangle formed by those interstate highways, as well as other areas also eligible under the DERI program. The eligible areas were expanded to become the Clean Transportation Zone (CTZ) in 2017, with the addition of the interstate highways and counties between the Laredo and Corpus Christi areas. From 2012 through August 2018, the CTTP and AFFP programs have funded 172 grants for a total of more than $34.5 million. Grants include the new construction or expansion of 69 natural gas fueling stations, 12 biodiesel fueling stations, 6 propane stations, and 85 electric charging stations. All grant funds have been awarded for the fiscal biennium of 2017–2018.

- The Texas Natural Gas Vehicle Grants Program provides grants for the replacement or repower of heavy- or medium-duty diesel- or gasoline-powered vehicles with natural gas- or liquid petroleum gas-powered vehicles and engines. Eligible vehicles must be operated within the CTZ counties. From 2009 through August 2017, the program funded 105 grants to replace 923 vehicles for a total of $41.9 million. These projects are projected to reduce more than 1,493 tons of NOX over the life of the projects. The program will be accepting applications through May 2019 or until all available funds have been awarded.

- The primary objective of the New Technology Implementation Grant Program is to offset the incremental cost of the implementation of existing technologies that reduce the emission of pollutants from facilities and other stationary sources that may also include energy-storage projects in Texas. From 2010 through August 2018, the program funded eight grants for a total of $10.6 million. The next New Technology Implementation Grant Program grant round is expected to open in September 2018.

- The Drayage Truck Incentive Program was established by the Legislature in 2013 to fund the replacement of drayage trucks operating at seaports and rail yards in Texas nonattainment areas with newer, less-polluting drayage trucks. In 2017, the legislature renamed the name the program the Seaport and Rail Yard Areas Emissions Reduction (SPRY) Program, and expanded the statutory criteria to include the replacement of cargo-handling equipment as well as drayage trucks. Through August 2018, the program funded 17 grants for the replacement of 77 trucks and pieces of cargo-handling equipment, for a total of $6.2 million. It is estimated that these projects will reduce more than 357 tons of NOX in eligible Texas seaports and rail yards over the life of the projects. The next SPRY Program grant round is expected to open in September 2018.

- The Light-Duty Motor Vehicle Purchase or Lease Incentive Program (LDPLIP) was established by the Legislature in 2013 to provide up to $2,500 for the purchase of a light-duty vehicle operating on natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas (lpg), or plug-in electric drive. Through its expiration, in August 2015, the program provided incentives for the purchase of 1,897 electric plug-in vehicles and 196 vehicles operating on compressed natural gas or propane, for a total $7.8 million. In 2017, the Legislature reinstated the LDPLIP to provide rebates of up to $5,000 for the purchase or lease of natural gas or lpg-powered light-duty vehicles, and up to $2,500 for light-duty vehicles powered by electric drives. The program is currently open and accepting applications through May 2019, or until all available funds have been awarded.

- The Governmental Alternative Fuel Fleet Program (GAFFP) was established by the Legislature in 2017 to help state agencies, political subdivisions, and transit or school transportation providers fund the replacement or upgrade of their vehicle fleets to alternative fuels, including natural gas, propane, hydrogen fuel cells, and electric. The Legislature required the TCEQ to consider the feasibility and benefits of implementing the GAFFP and, if feasible, allowed the commission to adopt rules governing the program and the eligibility of entities to receive grants. However, funding for this program was not included in the Appropriations Act. Therefore, implementation is not currently feasible.

TERP grants and activities are further detailed in a separate report, TERP Biennial Report to the Texas Legislature (TCEQ publication SFR-079/18).

Texas Clean School Bus Program

The Texas Clean School Bus Program (TCSBP) provided grants for technologies that reduce diesel-exhaust emissions inside the cabin of a school bus, as well as educational materials to school districts on other ways to reduce emissions, such as idling reduction. From 2008 to August 2017, the TCSBP used state and federal funds to reimburse approximately $29.8 million to retrofit 7,560 school buses in Texas. In 2017, the Legislature expanded the criteria for the TCSBP to also include grants for the replacement of older school buses with newer models. From September 2017 through August 2018, the TCSBP awarded approximately $2.9 million to replace 61 school buses across the state. An additional $3.1 million is expected to be awarded beginning September 2018 for the replacement of 66 school buses.

Texas Volkswagen Environmental Mitigation Program

In December 2017, Gov. Greg Abbott selected the TCEQ as the lead agency responsible for the administration of funds received from the Volkswagen State Environmental Mitigation Trust. A minimum of $209 million dollars will be made available for projects that mitigate the additional nitrogen oxides emissions resulting from specific vehicles using defeat devices to pass emissions tests. The TCEQ is currently developing a Beneficiary Mitigation Plan for Texas, as required by the trust, that will summarize how the funds allocated to Texas will be used. In general, funds provided under the trust must be awarded through grants to governmental and non-governmental entities in accordance with the priorities established in the Mitigation Plan.

Drive a Clean Machine

The Drive a Clean Machine program was established in 2007 as part of the Low Income Vehicle Repair Assistance, Retrofit, and Accelerated Vehicle Retirement Program (LIRAP) to repair or remove older, higher-emitting vehicles. The Drive a Clean Machine (DACM) program is available to qualifying vehicle owners in 16 participating counties in the areas of HGB, DFW, and Austin–Round Rock. The counties in these areas conduct annual inspections of vehicle emissions. From the program’s debut in December 2007 through May 2018, qualifying vehicle owners have received more than $218 million. This funding helped replace 64,509 vehicles and repair 45,153.

Following the governor’s veto of the appropriations funding for the LIRAP and the Local Initiative Projects program for fiscal biennium 2018–19, all 16 participating counties opted out and collection of the LIRAP fee has been terminated. Funding carried over from fiscal biennium 2016–17 appropriations may continue to be used for the DACM program until Aug. 31, 2019.

Local Initiative Projects

The Local Initiative Projects (LIP) program was established in 2007 to provide funding to counties participating in the LIRAP for implementation of air quality improvement strategies through local projects and initiatives. Projects are funded both by the TCEQ from LIRAP appropriations and through a dollar-for-dollar match by the local government, although the TCEQ may reduce the match for counties implementing programs to detect vehicle-emissions fraud (currently set at 25¢/dollar). From the LIP program’s debut in December 2007, more than $31 million has been appropriated to fund eligible projects in the participating counties. Recently funded projects include vehicle-emissions enforcement task forces; traffic-signal synchronization; and bus transit services.

Although all 16 counties participating in the LIRAP have opted out, LIP funding carried over from fiscal biennium 2016–17 appropriations may continue to be used by these counties for the LIP program until Aug. 31, 2019.

Environmental Research and Development

The TCEQ supports cutting-edge scientific research to expand knowledge about air quality in Texas. The agency’s Air Quality Research Program (AQRP) continues to be engaged in a range of projects that build on scientific research on air quality from the previous biennium.

The AQRP and the TCEQ sponsored a field campaign during May 2017 to study ozone in the San Antonio area. Detailed atmospheric chemistry and meteorology measurements were made at six sites in the area. Ongoing analysis of these data will allow the TCEQ to better understand ozone in San Antonio.

Other important air quality research carried out through the AQRP has included the following:

- Projects that examine the role of wildfires and agricultural burning upon air quality in Texas, including fires outside of Texas and the United States.

- A study of the activity data used to estimate NOX emissions from cars and trucks in Texas, and how locally derived data can contribute to these estimates.

- Improvements in the tools used to estimate biogenic volatile organic compound emissions in Texas.

In addition to research carried out through the AQRP, the TCEQ used grants and contracts to support ongoing air quality research. These are some of the many notable projects:

- A review-and-synthesis study examining atmospheric impacts of oil and gas development on ozone and particulate matter pollution in Texas.

- Analyses of biomass burning impacts on Texas air quality using two different modeling methods, with an emphasis on identifying exceptional events that may affect air quality.

- Updating emissions inventories for emissions from flash tanks, asphalt paving; ocean-going tanker-vessel lightering (i.e., transferring liquids from one tanker to another); aircraft; rail yard activity; and industrial, commercial, or institutional fuel use.

- Improving the boundary conditions used in ozone modeling in Texas by updating the model chemistry.

- Measurements of biogenic VOC emissions and improvements of the tools used to estimate those emissions both inside Texas and throughout the ozone-modeling domain.

The latest findings from these research projects help the state understand and appropriately address some of the challenging air quality issues faced by Texans because of changes to various standards for ambient air quality and other federal actions. These challenges are increasing, and addressing them will require continued emphasis on scientific understanding. This knowledge helps ensure that Texas adopts attainment strategies that are achievable, sound, and based on the most current science.