Agency Activities: Water Availability (FY2017-2018)

The following summarizes the agency’s activities regarding drought, water rights, groundwater management, evaluations of river basins without a watermaster, the Brazos watermaster, and Texas interstate river compacts. (Part of Chapter 2—Biennial Report to the 86th Legislature, FY2017-FY2018)

Water Availability

Managing Surface Water Rights

The TCEQ is charged with managing state surface water in Texas. One way the agency implements its authority is through permitting of surface water rights. The use of water for domestic or livestock purposes is considered a superior water right that does not require a permit. The TCEQ is responsible for protecting senior and superior water rights, as well as for ensuring that water right holders divert state water only in accordance with their permits.

Texas water law specifies that in times of shortage, permitted water rights will be administered based on the priority date of each water right, also known as the prior appropriation doctrine; that is, the earliest in time is senior. Additionally, exempt domestic and livestock uses are superior to permitted rights. Among permitted water right holders, the permit holders that received their authorization first (senior water rights) are entitled to take their water before water right holders that received their authorization on a later date (junior water rights). Senior or superior water right holders not able to take their authorized water can call on the TCEQ to enforce the priority doctrine (a priority call).

Under the TCEQ v. Texas Farm Bureau decision, the TCEQ will not be able to exempt any junior water rights based on public health, safety, or welfare concerns, including junior water rights used for municipal purposes or power generation, if suspension is necessary to satisfy a priority call by a senior or superior water right.

Managing Water Availability During Drought

Widespread drought conditions developed and persisted across Texas from 2009 through 2015. The drought of 2011 broke records, with 97 percent of the state in extreme or exceptional drought. By mid-2016, less than 2 percent of the state experienced abnormally dry conditions; however, in mid-2018, severe or worse drought conditions had returned to around 20 percent of Texas.

The TCEQ is engaged to respond to extreme drought. The agency’s focus on drought response and its activities include monitoring conditions across the state, expedited processing of drought-related water rights applications, priority call response, and participating in multi-disciplinary task force meetings. The TCEQ also communicates information about drought to state leaders, legislative officials, county judges, county extension agents, holders of water right permits, and the media.

In June, July, and August 2018, drought-alert letters were mailed to public water suppliers, water rights holders, county judges, and county extension agents in drought-affected areas to provide notification that dry conditions may persist in the coming months for some parts of Texas and that if a priority call is made, the TCEQ may have to suspend water rights in some areas of the state.

Drinking Water Systems

The Public Drinking Water Program is responsible for ensuring that the citizens of Texas receive a safe and adequate supply of drinking water. The TCEQ carries out this responsibility by implementing the Safe Drinking Water Act. All PWSs are required to register with the TCEQ, provide documentation to show that they meet state and federal requirements, and evaluate the quality of the drinking water.

Drought Response and Assistance for Public Water Systems

Drought-response activities are coordinated through the TCEQ’s Drought Team, a multidisciplinary agency group that began meeting in 2010. The team issues updates on the status of drought conditions and agency responses. Agencies invited to team meetings are partners such as the Texas Department of Emergency Management, Texas Department of Agriculture, and Texas Water Development Board.

In addition, the multi-disciplinary Emergency Drinking Water Task Force was formed by the Texas Division of Emergency Management and facilitated by the TCEQ to respond to drought emergencies at PWSs. Once the TCEQ was notified or became aware that a water system was within 180 days of running out of water, the task force informed the appropriate local and state officials, as well as the local TDEM district coordinator, who in turn notified the county emergency management coordinator, mayor, county judge, and appropriate state legislators. The Task Force met weekly at the height of the drought, and now—in 2018—meets monthly, to discuss the systems being tracked and opportunities for outreach and assistance.

The agency continues to monitor a targeted list of PWSs that have a limited or unknown supply of water remaining. Employees offer those systems financial, managerial, and technical assistance, such as identifying alternative water sources, coordinating emergency drinking-water planning, and finding possible funding for alternative sources of water. The TCEQ also engages in outreach and assistance—specifically targeting PWSs—to help prevent PWSs from running out of water. The agency contacts PWSs to urge implementation of drought contingency plans. TCEQ staff offer assistance to any PWS continuing to experience critical conditions.

From 2012 to the present, the TCEQ has provided technical assistance to more than 427 public water systems by expediting approximately 625 requests for reviews of plans and specifications for drilling additional wells, moving surface water intakes to deeper waters, and finding interconnections with adjacent water systems, without compromising drinking-water quality and the capacity of other systems.

In fiscal 2018, a total of 688 PWSs implemented mandatory water restrictions, while another 398 relied on voluntary measures to cut back on water use. For the complete list, see <www.tceq.texas.gov/goto/pws-restrictions>.

Exploring New Supplies through Alternative Treatment

With Texas’ population expected to reach almost 46 million by the year 2060, and given the lasting effects of the drought, Texans have had to plan far in advance to sustain their water needs. Because of these challenges, PWSs have begun to use less-conventional sources of water and the TCEQ began reviewing several innovative water-supply projects. The TCEQ has engineers and scientists with the expertise to guide PWSs through selecting innovative treatment technologies and receiving approval for those technologies while ensuring that the treated water is safe for human consumption.

One alternative involves not only reclaiming effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants for non-potable uses such as irrigation and industry, but also adding additional treatment to remove chemical and microbiological contaminants to prepare the effluent for direct potable reuse.

Another alternative for some communities is to treat saline or brackish groundwater. For this reason, the agency streamlined construction approval for PWSs asking to conduct brackish-water desalination. To further assist communities with decreased water supplies, the TCEQ offers other streamlined approval processes such as concurrent reviews of designs and models.

Marine desalination has been gaining attention as some communities seek to treat saline water to make it potable. In response, the 84th Texas Legislature passed House Bills 2031 and 4097 in 2015 to expedite permitting related to desalination of both marine seawater from the Gulf of Mexico and seawater from a bay or arm of the gulf. In 2016, the agency initiated a rulemaking to expedite permitting and related processes for such diversion of seawater and the discharge of both treated seawater and waste resulting from desalination, and to address industrial seawater desalination.

Water Rights Permitting

Water flowing in Texas creeks, rivers, lakes, and bays is state water. The right to use state water may be acquired through appropriation via permitting as established in state law. An authorization (permit or certificate of adjudication) is required to divert, use, or store state water or to use the bed and banks of a watercourse to convey water. However, there are several specific uses of state water that are exempt from the requirement to obtain a water right permit, such as domestic and livestock (D&L) purposes. For any new appropriation of state surface water, the Texas Water Code requires the TCEQ to determine whether water is available in the source of supply. Once obtained, a surface water authorization is perpetual, with exception to some temporary and term authorizations.

The TCEQ reviews permit applications for new appropriations of state water for administrative and technical requirements related to conservation, water availability, and the environment. In addition to new appropriation requests, the agency also reviews amendment applications and other applications including bed-and-bank authorizations, reuse, and temporary water rights. In fiscal 2017 and 2018, the agency processed 1,630 water rights actions, including new permits, amendments, water-supply contracts, and transfers of ownership.

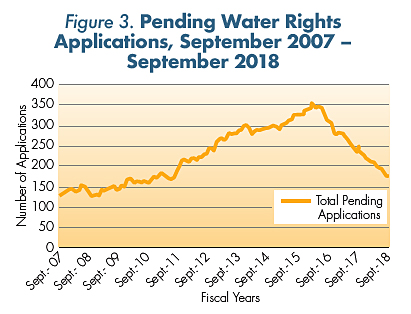

Major changes to state water policy (for example, developing environmental flow standards), drought, complex applications, and other projects can shift TCEQ water rights permitting staff from permitting activities. Beginning in 2007, several of these factors affected water rights processing. In September 2007, there were 127 pending water right applications. That number climbed to 355 in early 2016 and has since been reduced to 177 as of September 2018. Figure 3 shows the number of water right permit applications pending with the TCEQ from September 2007 to September 2018. This graph shows how changes to state water policy, drought, complex permits, and other projects affect water rights permitting during this timeframe.

During the last biennium, the TCEQ conducted a critical review of water rights permitting and change-of-ownership processes that resulted in changes. These changes included allocating additional personnel to the program, strongly encouraging pre-application meetings to assist applicants in developing more complete applications, limiting time extensions granted to applicants to respond to requests for information, and implementing return policies when an applicant is unresponsive. Internal application-tracking tools have also been implemented to streamline processes. This critical review is an iterative process with improvements continuing. In addition, the TCEQ has engaged in outreach efforts to help water right holders remain in compliance with statutory requirements for reporting water use. Whenever possible, the TCEQ has reached out to water rights stakeholders and has increased its presence and availability at water conferences and other events.

Fast Track Permitting

Not all water right applications require the same level of technical review. Reuse applications, applications that seek a new appropriation of water, and applications to move a diversion point (outside the Rio Grande) require a more intensive technical review.

In July 2016, the Water Rights Permitting program began a “Fast Track” pilot program for those “Other” applications. A separate, more streamlined process and dedicated staff allow Fast Track applications to be processed more quickly. Since the pilot program began, 219 Fast Track applications have been processed. Of those received after the program began, the average processing time is 213 days. The TCEQ continues to evaluate the Fast Track program to see which applications fit well in the program.

Changes of Ownership and Water Use Reports

The TCEQ processes ownership changes in support of water rights permitting statewide. Current ownership information ensures that proper notice information is received by water rights permit holders. Additionally, current owner information is critical to ensure that information is conveyed to the appropriate permit holder to achieve the desired effect of actions taken to meet a priority call during drought.

The TCEQ also requires the completion of Water Use Reports to support modeling efforts and enforcement of water rights. Water Use Reports are sent to water rights permit holders outside of Watermaster areas on Jan. 1 of each year and are due back to TCEQ on March 1. The return rate for these reports is between 75 and 85 percent of the reports mailed out, but this actually represents approximately 95 percent of the permitted water in the state.

Water Conservation and Drought Contingency Plans

The TCEQ is currently working to improve instructional material available on its website in preparation for the upcoming five-year review and May 1, 2019, submittal of water conservation and drought contingency plans. The TCEQ is engaged in outreach efforts to notify entities that are required to develop, implement, and submit Water Conservation Plans, Drought Contingency Plans, and Water Conservation Implementation Reports to the TCEQ every five years of the upcoming deadline.

Changes in Water Rights

In 2017, the 85th Texas Legislature passed four bills relating to surface water rights that required changes to the TCEQ’s rules. House Bill (HB) 1648 amended requirements relating to certain retail public utilities and their designation of a water conservation coordinator. HB 3735 amended TCEQ surface water application map requirements and codified the commission’s practice regarding consideration of the public welfare in water rights applications. Senate Bill (SB) 864 amended the notice requirements relating to alternate sources of water used in surface water rights applications. Finally, SB 1430 and HB 3735 required the TCEQ to create an expedited amendment process to change the diversion point for existing non-saline surface water rights when the applicant begins using desalinated seawater. The TCEQ implemented the requirements of these bills in a single rulemaking adopted in July 2018.

In 2018, the TCEQ revised water rights application forms and instructional material available on its website to assist applicants in developing more complete applications. The new application forms are resulting in applications that are more complete; thereby helping to reduce processing timeframes. The TCEQ continues to search for more improvements that will expedite permitting without neglecting any statutory responsibilities. Overall, these actions have resulted in increased production in water rights permitting and the total number of pending water right applications continues to decline.

Environmental Flows

In 2007, the Legislature passed two landmark measures relating to the development, management, and preservation of water resources, including the protection of instream flows and freshwater inflows. The measures changed how the state determines the flow that needs to be preserved in the watercourse for the environment, requiring the consideration of both environmental and other public interests.

The TCEQ adopted rules for environmental flow standards for Texas’ rivers and bays. The third rulemaking for the environmental flow standards was completed in February 2014. The TCEQ’s ongoing goal is to protect the flow standards—along with the interests of senior water-rights holders—in the agency’s water rights permitting process for new appropriations and amendments that increase the amount of water to be taken, stored, or diverted.

The Texas Instream Flow Program (TIFP) was established in 2001 before environmental flow standards were required, developed, and adopted into the water rights permitting process. The TIFP has been a collaboration between the TCEQ, the Texas Water Development Board, and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to collect and evaluate instream flow data and to conduct studies to determine instream flow conditions necessary to support a sound ecological environment in specific watersheds. These responsibilities have been replaced by the dynamic 2007 environmental flows process.

Final recommendations of instream flow studies of the lower San Antonio and middle and lower Brazos river basins were completed in fiscal 2018. Instream flow studies are concluding in the middle Trinity and lower Guadalupe river basins. Completion of the middle Trinity and lower Guadalupe studies will conclude the work of the TIFP.

Evaluations of River Basins without a Watermaster

Under the Texas Water Code, the TCEQ is required every five years to evaluate river basins that do not have a watermaster program to determine whether a watermaster should be appointed. Agency personnel are directed to report their findings and make recommendations to the commission.

In 2011, the TCEQ developed a schedule for conducting these evaluations, as well as criteria for developing recommendations. The TCEQ has completed one five-year cycle of evaluations. The agency is currently in the second five-year cycle. In 2017, the TCEQ evaluated the Colorado and Upper Brazos river basins along with the San Jacinto–Brazos, Brazos Colorado, and Colorado Lavaca coastal basins. In 2018, the TCEQ evaluated the Trinity and San Jacinto river basins, along with the Trinity San Jacinto and Neches Trinity coastal basins.

The commission did not create a watermaster program on its own motion at the conclusion of any evaluation year. In the first five-year cycle, the TCEQ expended approximately $570,000 total in staff time, travel costs, and other administrative costs to conduct evaluations. In the first year of the second five-year cycle, the agency expended approximately $170,000.

For more information, see Appendix D, “Evaluation of Water Basins in Texas without a Watermaster.”

Texas Interstate River Compacts

Texas is a party to five interstate river compacts. These compacts apportion the waters of the Canadian, Pecos, Red, and Sabine rivers and the Rio Grande between the appropriate states. Interstate compacts form a legal foundation for the equitable division of the water of an interstate stream with the intent of settling each state’s claim to the water.

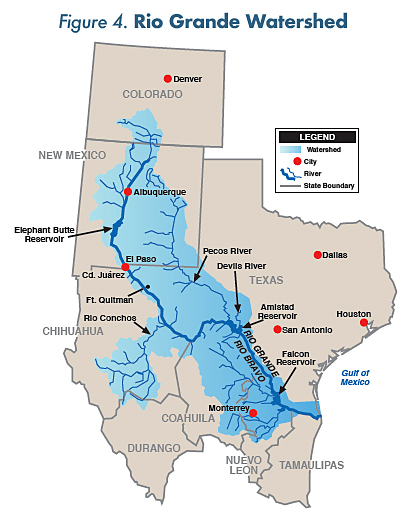

Rio Grande Compact

The Rio Grande Compact, ratified in 1939, divided the waters of the Rio Grande among the signatory states of Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas from its source in Colorado to Fort Quitman, Texas. The compact did not contain specific wording regarding the apportionment of water in and below Elephant Butte Reservoir. However, the compact was drafted and signed against the backdrop of the 1915 Rio Grande Project and a 1938 U.S. Bureau of Reclamation contract that referred to a division of 57 percent to New Mexico and 43 percent to Texas. The compact contains references and terms to ensure sufficient water to the Rio Grande Project.

The project serves the Las Cruces and El Paso areas and includes Elephant Butte Reservoir, along with canals and diversion works in New Mexico and Texas. The project water was to be allocated according to the 57:43 percent division, based on the relative amounts of project acreage originally identified in each state. Two districts receive project water: Elephant Butte Irrigation District (EBID), in New Mexico, and El Paso County Water Improvement District No. 1 (EP #1), in Texas. The latter supplies the city of El Paso with about half of its water.

In 2008, after 20 years of negotiations, the two districts and the Bureau of Reclamation completed an operating agreement for the Rio Grande Project. The agreement acknowledged the 57:43 percent division of water and established a means of accounting for the allocation. The agreement was a compromise to resolve major issues regarding the impact of large amounts of groundwater development and pumping in New Mexico that affected water deliveries to Texas.

But significant compliance issues continue regarding New Mexico’s water use associated with the Rio Grande Compact. In 2011, New Mexico took action in federal district court to invalidate the 2008 operating agreement. In response to the lawsuit and in coordination with the Legislative Budget Board and the Attorney General’s Office, the Rio Grande Compact Commission of Texas hired outside counsel and technical experts with specialized experience in interstate water litigation to protect Texas’ share of water.

In January 2013, Texas filed litigation with the U.S. Supreme Court. A year later, the Supreme Court granted Texas’ motion and accepted the case. Subsequently, the United States filed a motion to intervene as a plaintiff on Texas’ side, which was granted.

As Texas develops information to support its position, evidence grows that New Mexico’s actions have significantly affected, and will continue to affect, water deliveries to Texas. On Nov. 3, 2014, the Supreme Court appointed a special master in this case with authority to fix the time and conditions for the filings of additional pleadings, to direct subsequent proceedings, to summon witnesses, to issue subpoenas, and to take such evidence as may be introduced. The special master was also directed to submit reports to the Supreme Court as he may deem appropriate.

A “special master” is appointed by the Supreme Court to carry out actions on its behalf such as the taking of evidence and making rulings. The Supreme Court can then assess the special master’s ruling much as a normal appeals court would, rather than conduct the trial itself. This is necessary as trials in the United States almost always involve live testimony and it would be too unwieldy for nine justices to rule on evidentiary objections in real time.

Motions to Intervene filed by EP#1 and EBID were referred to the special master. Following a hearing on the motions conducted August 19–20, 2016, the special master filed his First Interim Report with the Supreme Court on Feb. 13, 2017. He recommended denying the motions to intervene filed by EP#1 and EBID as well as New Mexico’s motion to dismiss. The First Interim Report was also very favorable to Texas’ position.

The Supreme Court ruled on Oct. 10, 2017: the motion of New Mexico to dismiss Texas’s complaint was denied; the motions of EBID and EP#1 to intervene were denied; the motions of New Mexico State University and New Mexico Pecan Growers for leave to file briefs as amicus curiae were granted. The exception of the United States and the first exception of Colorado to the First Interim Report of the Special Master were heard during oral arguments by the Supreme Court on Jan. 8, 2018. On March 5, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the United States may pursue the compact claims it has pleaded in the litigation and all other exceptions were denied.

A new special master was appointed by the Supreme Court on April 2, 2018. New Mexico filed a response to Texas’ complaint on May 22, 2018, denying the allegations and filed counterclaims against Texas and the United States. Responses to New Mexico were submitted on July 20, 2018. It is anticipated that discovery will commence Sept. 1, 2018, with a trial expected in the spring of 2020.

International Treaties

Two international treaties have a major impact on water supplies available to Texas. The 1906 convention between the United States and Mexico apportions the waters of the Rio Grande Basin above Fort Quitman, Texas, while the 1944 treaty between the United States and Mexico apportions the waters of the basin below Fort Quitman.

Mexico continues to under-deliver water to the United States under the 1944 Treaty. Mexico does not treat the United States as a water user and only relies on significant rainfalls to make deliveries of water. This stands in contrast to the manner in which the United States treats Mexico with regard to the Colorado River. In fact, the United States has always supplied Mexico its annual allocation from the Colorado River. The Colorado River and the Rio Grande are both covered by the same 1944 water treaty. Efforts continue through the Texas congressional delegation to address this problem.

A related issue concerns the accounting of waters in the Rio Grande at Fort Quitman. While the 1906 convention clearly granted 100 percent of all waters below El Paso to Fort Quitman to the United States, the International Boundary and Water Commission has allocated the waters equally between the United States and Mexico.

Groundwater

The TCEQ is responsible for delineating and designating priority groundwater management areas (PGMAs) and creating groundwater conservation districts in response to landowner petitions or through the PGMA process.

In 2019, the TCEQ and the Texas Water Development Board will submit a joint legislative report that details activities in fiscal biennium 2017–18 relating to PGMAs and the creation and operation of groundwater conservation districts.

Groundwater conservation districts (GCDs), each governed by a locally selected board of directors, are the state’s preferred method of groundwater management. Under the Texas Water Code, GCDs are authorized and required to issue permits for water wells, develop a management plan, and adopt rules to implement the plan. The plan and the “desired future conditions” for a groundwater management area must be readopted and approved at least once every five years. The TCEQ actively monitors and ensures GCD compliance to meet requirements for adoption and re-adoption of management plans.

The TCEQ also has responsibility for supporting the activities of the interagency Texas Groundwater Protection Committee (TGPC). Texas Water Code, Sections 26.401–26.408, enacted by the 71st Texas Legislature (1989), established non-degradation of the state’s groundwater resources as the goal for all state programs. The same legislation created the TGPC to bridge gaps between existing state groundwater programs and to optimize groundwater quality protection by improving coordination among agencies involved in groundwater activities.

Three of the TGPC’s principal mandated activities are:

- Developing and updating a comprehensive groundwater protection strategy for the state.

- Publishing an annual report on groundwater monitoring activities and cases of documented groundwater contamination associated with activities regulated by state agencies.

- Preparing and publishing a biennial report to the legislature describing these activities, identifying gaps in programs, and recommending actions to address those gaps.