Agency Activities: Water Quality (FY2017-2018)

The following summarizes the agency’s activities regarding development of surface water quality and drinking water standards, water quality monitoring, assessing surface water data, restoring water quality, bay and estuary programs, stormwater permitting, utility services, and the Clean Rivers Program. (Part of Chapter 2—Biennial Report to the 86th Legislature, FY2017-FY2018)

Water Quality

Developing Surface Water Quality Standards

Texas Surface Water Quality Standards

Under the federal Clean Water Act, every three years the TCEQ is required to review and, if appropriate, revise the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards. These standards are the basis for establishing discharge limits in wastewater permits, setting instream water quality goals for total maximum daily loads, and establishing criteria to assess instream attainment of water quality.

Water quality standards are set for major streams and rivers, reservoirs, and estuaries based on their specific uses: aquatic life, recreation, drinking water, fish consumption, and general. The standards establish water quality criteria for temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, salts, bacterial indicators for recreational suitability, and a number of toxic substances.

The commission revised its water quality standards in 2018. Major revisions included:

- A new single sample criterion for coastal recreation waters as mandated by the BEACH Act

- Revisions to toxicity criteria to incorporate new data on toxicity effects and local water quality characteristics that affect toxicity.

- Numerous revisions and additions to the uses and criteria of individual water bodies to incorporate new data and the results of recent use-attainability analyses.

The revised standards must be approved by the EPA before being applied to activities related to the Clean Water Act. Although federal review of portions of the 2010 and the 2014 standards has yet to be completed, the TCEQ proceeded with its 2017 triennial standards review. The commission approved the 2018 Texas Surface Water Quality Standards in February 2018. It was sent to the EPA and is awaiting approval.

Use-Attainability Analyses

The Surface Water Quality Standards Program also coordinates and conducts use-attainability analyses to develop site-specific uses for aquatic life and recreation. The UAA assessment is often used to re-evaluate designated or presumed uses when the existing standards may need to be revised for a water body. As a result of aquatic life UAAs, site-specific aquatic-life uses and dissolved-oxygen criteria were adopted in the 2018 revision of the standards for individual water bodies.

In 2009, the TCEQ developed recreational UAA procedures to evaluate and more accurately assign levels of protection for water recreational activities such as swimming and fishing. Since then, the agency has initiated more than 120 UAAs to evaluate recreational uses of water bodies that have not attained their existing criteria. Using results from recreational UAAs, the TCEQ is proposing site-specific contact-recreation criteria for numerous individual water bodies in the 2018 Texas Surface Water Quality Standards revision.

Clean Rivers Program

The Clean Rivers Program administers and implements a statewide framework set out in Texas Water Code, Section 26.0135. This state program works with 15 regional partners (river authorities and others) to collect water quality samples, derive quality-assured data, evaluate water quality issues, and provide a public forum for prioritizing water quality issues in each Texas river basin. This program provides 60–70 percent of the data available in the state’s surface water quality database used for water-resource decisions, including revising water quality criteria, identifying the status of water quality, and supporting the development of projects to improve water quality.

Water Quality Monitoring

Surface water quality is monitored across the state in relation to human-health concerns, ecological conditions, and designated uses. The resulting data form a basis for policies that promote the protection and restoration of surface water in Texas. Special projects contribute water quality monitoring data and information on the condition of biological communities. This provides a basis for developing and refining criteria and metrics used to assess the condition of aquatic resources.

Coordinated Routine Monitoring

Each spring, TCEQ staff meets with various water quality organizations to coordinate monitoring efforts for the upcoming fiscal year. The TCEQ prepares the guidance and reference materials, and the Texas Clean Rivers Program partners coordinate the local meetings. The available information is used by participants to select stations and parameters that will enhance the overall coverage of water quality monitoring, eliminate duplication of effort, and address basin priorities.

The coordinated monitoring network, which consists of about 1,800 active stations, is one of the most extensive in the country. Coordinating the monitoring among the various participants ensures that available resources are used as efficiently as possible.

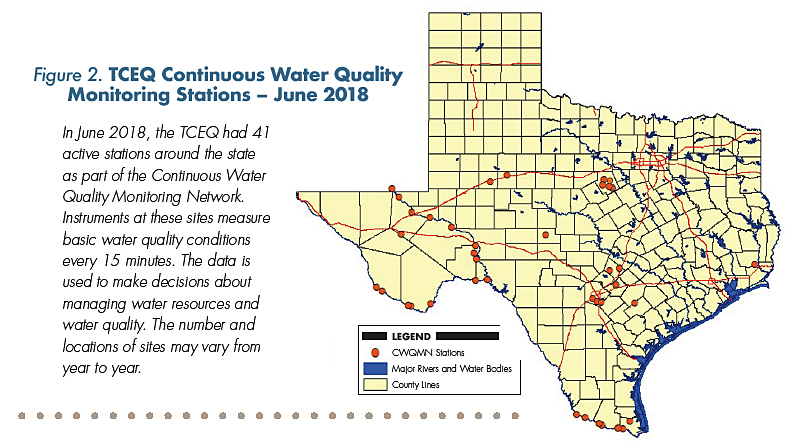

Continuous Water Quality Monitoring

The TCEQ has developed—and continues to refine—a network of continuous water quality monitoring sites on priority water bodies. The agency maintains 40 to 50 sites in its Continuous Water Quality Monitoring Network (CWQMN). At these sites, instruments measure basic water quality conditions every 15 minutes.

CWQMN monitoring data may be used by the TCEQ or other organizations to make decisions about water-resource management, as well as to target field investigations, evaluate the effectiveness of water quality management programs such as TMDL implementation plans and watershed-protection plans, characterize existing conditions, and evaluate spatial and temporal trends. The data are posted at <www.waterdatafortexas.org .

The CWQMN is used to guide decisions on how to better protect certain segments of rivers or lakes. For example, the TCEQ developed a network of 15 CWQMN sites on the Rio Grande and the Pecos River, primarily to monitor levels of dissolved salts to protect the water supply in Amistad Reservoir. The Pecos River CWQMN stations also supply information on the effectiveness of the Pecos River Watershed Protection Plan. These stations are operated and maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey through cooperative agreements with the TCEQ and the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board. Another use of such data is development of water quality models.

Assessing Surface Water Data

Every even-numbered year, the TCEQ assesses water quality to determine which water bodies meet the surface water quality standards for their designated uses, such as contact recreation, support of aquatic life, or drinking-water supply. Data associated with 200 different water quality parameters are reviewed to conduct the assessment. These parameters include physical and chemical constituents, as well as measures of biological integrity.

The assessment is published on the TCEQ website and submitted as a draft to the EPA as the Texas Integrated Report for Clean Water Act Sections 305(b) and 303(d) (found at <www.tceq.texas.gov/waterquality/assessment>).

The Integrated Report evaluates conditions during the assessment period and identifies the status of the state’s surface waters in relation to the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards. Waters that do not regularly attain one or more of the standards may require action by the TCEQ and are placed on the 303(d) List of Impaired Water Bodies for Texas (part of the report). The EPA must approve this list before its implementation by the TCEQ’s water quality management programs.

Because of its large number of river miles, Texas can monitor only a portion of its surface water bodies. The major river segments and those considered at highest risk for pollution are monitored and assessed regularly. The 2014 Integrated Report was approved by the EPA in November 2015. In developing the report, water quality data was evaluated from 5,086 sites on 1,409 water bodies. The draft 2016 Integrated Report is currently in the TCEQ approval process and the draft 2018 Integrated Report is under development.

Restoring Water Quality

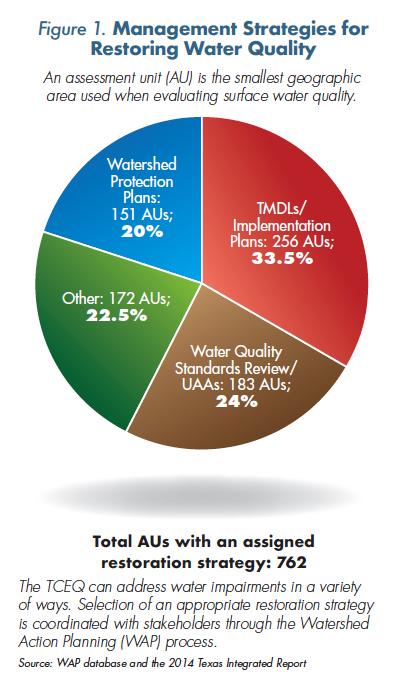

Watershed Action Planning

Water quality planning programs in Texas have responded to the challenges of maintaining and improving water quality by developing new approaches to addressing water quality issues in the state. Watershed Action Planning (WAP) is a process for coordinating, documenting, and tracking the actions necessary to protect and improve the quality of the state’s streams, lakes, and estuaries. The major objectives are:

- To fully engage stakeholders in determining the most appropriate action to protect or restore water quality.

- To improve access to state agencies’ decisions about water quality management and increase the transparency of that decision making.

- To improve the accountability of state agencies responsible for protecting and improving water quality.

Leading the WAP process are the TCEQ, the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board, and the Texas Clean Rivers Program. Involving stakeholders, especially at the watershed level, is key to the success of the WAP process.

Total Maximum Daily Load Program

The Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Program is one of the agency’s mechanisms for improving the quality of impaired surface waters. A TMDL is the total amount (or load) of a single pollutant that a receiving water body can assimilate within a 24-hour period and still maintain water quality standards. A rigorous scientific process is used to arrive at practicable targets for the pollutant reductions in TMDLs.

This program works with the agency’s water quality programs, other governmental agencies, and watershed stakeholders during the development of TMDLs and related implementation plans.

Bacteria TMDLs

Bacteria from human and animal wastes can indicate the presence of disease-causing microorganisms that pose a threat to public health. People who swim or wade in waterways with high concentrations of bacteria have an increased risk of contracting gastrointestinal illnesses. High bacteria concentrations can also affect the safety of oyster harvesting and consumption.

Of the 589 impairments listed in the 2014 Integrated Report for surface water segments in Texas, about half are for bacterial impairments to recreational water uses.

The TMDL Program has developed an effective strategy for developing TMDLs that protects recreational safety. The strategy relies on the engagement and consensus of the communities in the affected watersheds. Other actions are also taken to address bacteria impairments, such as recreational use–attainability analyses that ensure that the appropriate contact-recreation use is in place, as well as watershed-protection plans developed by stakeholders and primarily directed at nonpoint sources.

Implementation Plans

While a TMDL analysis is being completed, stakeholders are engaged in the development of an Implementation Plan (I-Plan), which identifies the steps necessary to improve water quality. These I-Plans outline three to five years of activities, indicating who will carry them out, when they will be done, and how improvement will be gauged. The time frames for completing I-Plans are affected by stakeholder resources and when stakeholders reach consensus. Each plan contains a commitment by the stakeholders to meet periodically to review progress. The plan is revised to maintain sustainability and to adjust to changing conditions.

Programmatic and Environmental Success

Since 1998, the TCEQ has been developing TMDLs to improve the quality of impaired water bodies on the federal 303(d) List, which identifies surface waters that do not meet one or more quality standards. In all, the agency has adopted 279 TMDLs for 196 water bodies in the state.

Based on a comparison of the 2012 and the 2014 Integrated Reports, water quality standards were attained for five impaired assessment units addressed by the TMDL Program.

From September 2014 to June 2018, the commission adopted TMDLs to address instances where bacteria had impaired the contact-recreation use. TMDLs were adopted for 10 surface water body segments consisting of 310 assessment units. A TMDL is developed for each assessment unit: Jarbo Bayou (one), Tres Palacios Creek (one), Upstream of Mountain Creek Lake (four), Town and Quinlan creeks (two), and Aransas River and Poesta Creek (two). During that time, the commission also approved one I-Plan, for Tres Palacios Creek. The commission approved Jarbo Bayou, Town and Quinlan creeks, Aransas River and Poesta Creek, and Upstream of Mountain Creek Lake to join existing I-Plans.

The Greater Trinity River Bacteria TMDL I-Plan is an example of successful community engagement to address bacteria impairments. Development of the I-Plan occurred through a stakeholder-driven process that included active public participation. Stakeholders engaged in the process represented a broad spectrum of authorities and interests including government, agriculture, business, conservation groups, and the public. The I-Plan identifies nine strategies for activities that address four TMDL projects.

Nonpoint Source Program

The Nonpoint Source (NPS) Program administers the provisions of Section 319 of the federal Clean Water Act. Section 319 authorizes grant funding for states to develop projects and implement NPS management strategies to maintain and improve water quality conditions.

The TCEQ, in coordination with the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board (TSSWCB), manages NPS grants to implement the long and short-term goals identified in the Texas NPS Management Program. The NPS Program annual report documents progress in meeting these goals.

The NPS grant from the EPA is split between the TCEQ (to address urban and non-agricultural NPS pollution) and the TSSWCB (to address agricultural and silvicultural NPS pollution). The TCEQ receives $3 to $4 million annually. About 60 percent of overall project costs are federally reimbursable; the remaining 40 percent comes from state or local matching. In fiscal 2018, $3.8 million was matched with $2.5 million, for a total of $6.3 million.

The TCEQ solicits applications to develop projects that contribute to the NPS Program management plan. Typically, 10 to 20 applications are received, reviewed, and ranked each year. Because the number of projects funded depends on the amount of each contract, the number fluctuates. Fourteen projects were selected in fiscal 2017, and 16 in fiscal 2018. Half of the federal funds awarded must be used to implement watershed-based plans, comprising activities that include public outreach and education, low-impact development, the construction and implementation of best management practices, and the inspection and replacement of on-site septic systems.

The NPS Program also administers provisions of Section 604(b) of the federal Clean Water Act. These funds are derived from State Revolving Fund appropriations under Title VI of the act. Using a legislatively mandated formula, money is passed through to councils of governments for water quality planning. The program received $617,000 in funding from the EPA in fiscal 2017 and $612,000 in fiscal 2018.

Bay and Estuary Programs

The estuary programs are non-regulatory, community-based programs focused on conserving the sustainable use of bays and estuaries in the Houston-Galveston and Coastal Bend bays regions through implementation of locally developed comprehensive conservation management plans. Plans for Galveston Bay and the Coastal Bend bays were established in the 1990s by a broad-based group of stakeholders and bay user groups. These plans strive to balance the economic and human needs of the regions.

The plans are implemented by two different organizations: the Galveston Bay Estuary Program, which is a program of the TCEQ, and the Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program, which is managed by a nonprofit authority established for that purpose. The TCEQ partially funds the CBBEP.

Additional coastal activities at the TCEQ include:

- Participating in the Gulf of Mexico Alliance, a partnership linking Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The TCEQ contributes staff time to implement the Governors’ Action Plan, focusing on water resources and improved comparability of data collection among the states.

- Serving on the Coastal Coordination Advisory Committee and participating in the implementation of the state’s Coastal Management Program to improve the management of coastal natural resource areas and to ensure long-term ecological and economic productivity of the coast.

- Directing, along with the General Land Office and the Railroad Commission of Texas, the allocation of funds from the Coastal Impact Assistance Program.

- Working with the General Land Office to gain full approval of the Coastal Nonpoint Source Program, which is required under the Coastal Zone Act Reauthorization Amendments.

Galveston Bay Estuary Program

The GBEP provides ecosystem-based management that strives to balance economic and human needs with available natural resources in Galveston Bay and its watershed. Toward this goal, the program fosters cross-jurisdictional coordination among federal, state, and local agencies and groups, and cultivates diverse, public-private partnerships to implement projects and build public stewardship.

GBEP priorities include:

- coastal habitat conservation

- public awareness and stewardship

- water conservation

- stormwater quality improvement

- monitoring and research

During fiscal 2017 and 2018, the GBEP worked to preserve wetlands and important coastal habitats that will protect the long-term health and productivity of Galveston Bay. To inform resource managers, the program conducted ecosystem-based monitoring and research, and worked with partners to fill data gaps. The GBEP collaborated with local stakeholders to create watershed-protection plans and to implement water quality projects. Its staff began updating the Galveston Bay Plan through a collaborative stakeholder process, and also continued to develop the Back the Bay campaign, which strives to increase public awareness and stakeholder involvement, and reinforce the priorities of the Galveston Bay Plan.

In fiscal 2017 and 2018, about 2,586 acres of coastal wetlands and other important habitats were protected, restored, and enhanced. Since 2000, the GBEP and its partners have protected, restored, and enhanced a total of 29,713 acres of important coastal habitats.

Through collaborative partnerships established by the program, approximately $5.84 in private, local, and federal contributions was leveraged for every $1 the state dedicated to the program.

Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program

During fiscal 2017 and 2018, the CBBEP implemented 59 projects, including habitat restoration and protection in areas totaling 2,913 acres. Based in the Corpus Christi area, the CBBEP is a voluntary partnership that works with industry, environmental groups, bay users, local governments, and resource managers to improve the health of the bay system. In addition to receiving program funds from local governments, private industry, the TCEQ, and the EPA, the CBBEP seeks funding from private grants and other governmental agencies. In the last two years, the CBBEP secured $2,833,504 in additional funds to leverage TCEQ funding.

CBBEP priority issues focus on human uses of natural resources, freshwater inflows, maritime commerce, habitat loss, water and sediment quality, and education and outreach. The CBBEP has also become active in water and sediment quality issues. The CBBEP’s goal is to address 303(d)-listed segments so that they meet state water quality standards.

Other areas of focus:

- Conserving and protecting wetlands and wildlife habitat through partnerships with private landowners.

- Restoring the Nueces River Delta for the benefit of fisheries, wildlife habitat, and freshwater conservation.

- Environmental education and awareness for more than 8,000 students and teachers annually at the CBBEP Nueces Delta Preserve by delivering educational experiences and learning through discovery, as well as scientific activities.

- Enhancement of colonial-waterbird rookery islands by implementing predator control, habitat management, and other actions to help stem the drop in populations of nesting coastal birds in the Coastal Bend and the Lower Laguna Madre.

- Supporting the efforts of the San Antonio Bay Partnership to better characterize the San Antonio Bay system and to develop and implement management plans that protect and restore wetlands and wildlife habitats.

Drinking Water

Of the approximately 7,000 public water systems (PWSs) in Texas, about 4,650 are community systems, mostly operated by cities. These systems serve about 97 percent of Texans. The rest are non-community systems—such as those at schools, churches, factories, businesses, and state parks.

The TCEQ makes data tools available online so the public can find information on the quality of locally produced drinking water. The Texas Drinking Water Watch at <www.tceq.texas.gov/goto/dww> provides analytical results from the compliance sampling of PWSs. In addition, the Source Water Assessment Viewer at <www.tceq.texas.gov/gis/swaview> shows the location of the sources of drinking water. The viewer also allows the public to see any potential sources of contamination, such as an underground storage tank.

All PWSs are required to monitor the levels of contaminants present in treated water and to verify that each contaminant does not exceed its maximum contaminant level, action level, or maximum residual disinfection level—the highest level at which a contaminant is considered acceptable in drinking water for the protection of public health.

In all, the EPA has set standards for 102 contaminants in the major categories of microorganisms, disinfection by-products, disinfectants, organic and inorganic chemicals, and radionuclides. The most significant microorganism is coliform bacteria, particularly fecal coliform. The most common chemicals of concern in Texas are disinfection by-products, arsenic, fluoride, and nitrate.

More than 56,000 water samples are analyzed each year just for chemical compliance. Most of the chemical samples are collected by contractors and then submitted to an accredited laboratory. The analytical results are sent to the TCEQ and the PWSs.

Each year, the TCEQ holds a free symposium on public drinking water, which typically draws about 800 participants. The agency also provides technical assistance to PWS to ensure that consumer confidence reports are developed correctly.

Any PWS that fails to have its water tested or reports test results incorrectly faces a monitoring or reporting violation. When a PWS has significant or repeated violations of state regulations, the case is referred to the TCEQ’s enforcement program.

Table 4. Violations of Drinking-Water Regulations

| Fiscal 2017 | Fiscal 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Enforcement Orders | 324 | 360 |

| Assessed Penalties | $328,533 | $398,343 |

| Offsets by SEPs | $12,472 | $23,836 |

Note: The numbers of public-water-supply orders reflect enforcement actions from all sources in the agency.

The EPA developed the Enforcement Response Policy and the Enforcement Targeting Tool for enforcement targeting under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The TCEQ uses this tool to identify PWSs with the most serious health-based or repeated violations and those that show a history of violations of multiple rules. This strategy brings the systems with the most significant violations to the top of the list for enforcement action, with the goal of returning those systems to compliance as quickly as possible.

More than 98 percent of the state’s population is served by a PWS producing water that meets or exceeds the National Primary Drinking Water Standards.

Review of Engineering Plans and Specifications

PWSs are required to submit engineering plans and specifications for new water systems or for improvements to existing systems. The plans must be reviewed by the TCEQ before construction can begin. In fiscal 2017, the TCEQ completed compliance review of 2,305 engineering plans for PWSs; in fiscal 2018, 2,396.

The agency strives to ensure that all water and sewer systems have the capability to operate successfully. The TCEQ contracts with the Texas Rural Water Association to assist utilities with financial, managerial, and technical expertise. About 1,099 assignments were made through this contract in fiscal 2017, and 1,307 assignments in fiscal 2018.

The agency reviews the creation of applications for general-law water districts and bond applications for water districts to fund water, sewer, and drainage projects. In fiscal 2017, the agency reviewed 576 water-district applications; in fiscal 2018, 514.

Wastewater Permitting

The Texas Pollutant Discharge Elimination System was created in 1998, when the EPA transferred the authority of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System for water quality permits in the state to Texas. The TPDES program issues municipal, industrial, and stormwater permits.

Industrial and Municipal Individual Permits

Industrial wastewater permits are issued for the discharge of wastewater generated from industrial activities. In fiscal 2017, the TCEQ issued 139 industrial wastewater permits; in fiscal 2018, 138. Municipal wastewater permits are issued for the discharge of wastewater generated from municipal and domestic activities. In fiscal 2017, the TCEQ issued 654 municipal wastewater permits; in fiscal 2018, 635.

Stormwater Permits

Authorization for stormwater discharges are primarily obtained through one of three types of general permits: industrial, construction, and municipal. The TCEQ receives thousands of applications a year for coverage. To handle the growing workload, the agency has introduced online applications for some of these permitting and reporting functions.

Industry

The multi-sector general permit regulates stormwater discharges from industrial facilities. Facilities authorized under this general permit must develop and implement a stormwater pollution prevention plan, conduct regular monitoring, and use best management practices to reduce the discharge of pollutants in stormwater. The TCEQ receives about 167 notices of intent, 75 no-exposure certifications, and 17 notices of termination a month for industrial facilities.

Construction

The construction general permit regulates stormwater runoff associated with construction activities, which include clearing, grading, or excavating land at building projects. Construction disturbing five or more acres is labeled a “large” activity, while construction disturbing one acre or more but less than five acres is termed “small.” The TCEQ currently receives about 643 notices of intent and 386 notices of termination a month for large construction activities.

Municipal

The TCEQ also regulates discharges from municipal separate storm-sewer systems (MS4s). This category applies to a municipality’s system of ditches, curbs, gutters, and storm sewers that collect runoff, including controls for drainage from state roadways. The TCEQ has issued 23 individual MS4 permits and 583 MS4s are authorized under a general permit. MS4s must develop and implement a stormwater management plan.

Table 5. Stormwater General Permits

| Applications Affected (issued) | Applications Received (monthly average) | Applications Received (total) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2017 | Fiscal 2018 | Fiscal 2017 | Fiscal 2018 | Fiscal 2017 | Fiscal 2018 | |

| Industrial (facilities)a | 8,581 | 2,675 | 186 | 126 | 9,678 | 1,514 |

| Construction (large sites) | 7,801 | 16,471 | 684 | 1,334 | 8,211 | 16,019 |

| MS4s (public entities) | 13 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 7 |

a Includes No-Exposure Certifications.