Chapter 2: Agency Activities

On this page:

Enforcement

Environmental Compliance

In a typical year, TCEQ conducts about 108,000 routine investigations and investigates about 4,700 complaints to assess compliance with environmental laws.

The TCEQ enforcement process begins when a violation is discovered during an investigation at a regulated entity’s location, through staff review of records at agency offices, or because of a complaint from the public that TCEQ subsequently verifies is a violation. Enforcement actions may also be triggered after submission of citizen-collected evidence.

When environmental laws are violated, TCEQ has the authority in administrative cases to levy penalties up to the statutory maximum (up to $25,000 for some programs) per day, per violation. TCEQ can also refer cases to the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) for civil prosecution. These civil judicial cases also carry penalties of up to $25,000 per day, per violation.

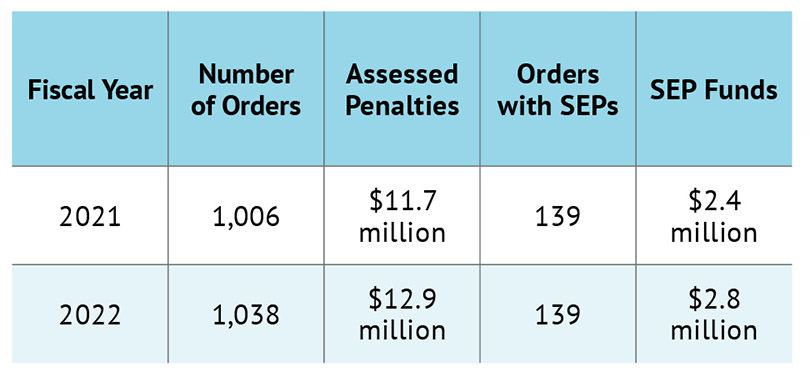

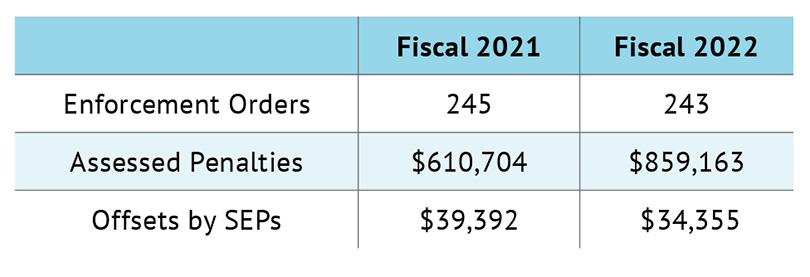

In fiscal 2021, TCEQ issued 1,006 administrative orders in which respondents were assessed over $7.5 million in penalties and over $2.4 million for Supplemental Environmental Projects (SEP) (see below). The average number of days from initiation of an enforcement action to completion (order approved by the commission) was 351 days.

In fiscal 2022, TCEQ issued 1,038 administrative orders, which required payments of over $7.9 million in penalties and over $2.8 million for SEPs. The average number of days from initiation of an enforcement action to completion was 405 days. Orders approved by the commission that have become effective are posted on TCEQ’s website, as are pending orders not yet presented to the commission.

In fiscal 2021, the OAG obtained 21 judicial orders in cases referred by TCEQ or in which TCEQ was a party. These judgments resulted in more than $16.5 million in civil penalties. In fiscal 2022, 24 OAG judgements resulted in more than $6.8 million in civil penalties.

You can find additional enforcement statistics in TCEQ’s annual enforcement report at www.tceq.texas. gov/goto/aer.

Supplemental Environmental Projects

Rather than being assessed a monetary penalty, regulated entities may be able to direct some of the penalty dollars towards a SEP that would be beneficial for the community where the environmental offense occurred. Such a project must reduce or prevent pollution, enhance the environment, or raise public awareness of environmental concerns.

A regulated entity that meets program requirements may propose a SEP from TCEQ’s list of preapproved projects or a custom SEP if the proposed project is environmentally beneficial and the party that would be performing the project was not already obligated or planning to perform the activity before the violation occurred. Additionally, the activity covered by a SEP must go beyond what is already required by state and federal environmental laws.

Table 1. TCEQ Enforcement Orders

Local governments cited in enforcement actions may use SEP money to achieve compliance with environmental laws or to remediate the harm caused by the violations in the case by proposing a compliance SEP. TCEQ may offer this option to governmental authorities such as school districts, counties, municipalities, and water districts.

Except for a compliance SEP, a SEP cannot be used to remediate a violation or any environmental harm that is caused by a violation or to correct any illegal activity that led to an enforcement action.

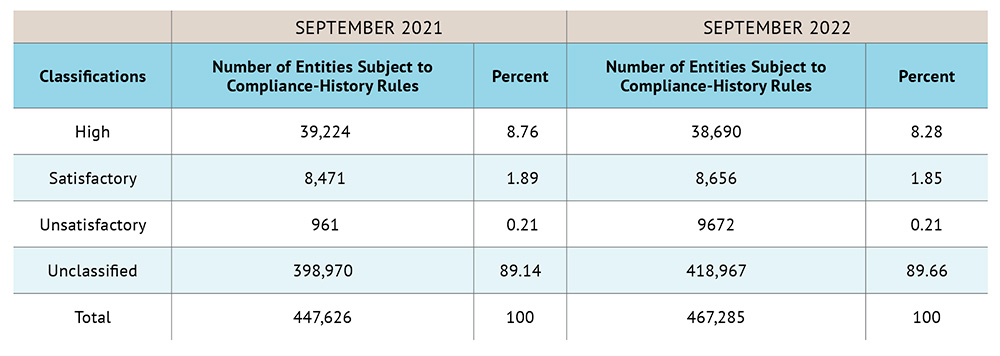

Compliance History

Each year, TCEQ rates the compliance history of every owner or operator of a facility that is regulated under certain state environmental laws. An evaluation standard has been used to assign a rating to approximately 430,000 entities regulated by TCEQ that are subject to the compliance history rules. The ratings take into consideration prior enforcement orders, court judgments, consent decrees, criminal convictions, and notices of violation, as well as investigation reports, notices, and disclosures submitted per the Texas Environmental, Health, and Safety Audit Privilege Act. Agency-approved environmental management systems and participation in agency-approved voluntary pollution-reduction programs are also considered.

You can find more information about this process at www.tceq.texas.gov/goto/history.

COMPLIANCE HISTORY RULE UPDATE

As a result of several large emergency industrial accidents over the past few years that caused significant impacts to public health and the environment, the commission approved a revision to the compliance history rules. The executive director may now initially designate a site’s compliance history classification as “under review” and then later reclassify it to “suspended” if exigent circumstances exist due to a significant emergency event at the site. This could include major explosions or fires that cause significant community disruption or commitment of emergency response resources by federal or state governmental authorities. This is codified in Title 30, Texas Administrative Code, Section 60.4 and became effective on June 23, 2022.

Table 2. Compliance-History Designations

Critical Infrastructure

The Critical Infrastructure Division (CID) combines elements that are critical to TCEQ’s responsibilities under the Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan. The division seeks to ensure that regulated critical infrastructures—essential to the state and its residents—maintain compliance with environmental regulations, and to support these critical infrastructures during disasters. Support during disasters includes not only responding to disasters, but also aiding in recovery from them.

In fiscal 2021 and fiscal 2022, CID’s programs included: Homeland Security, Dam Safety, Radioactive Materials Compliance and Chemical Reporting, and Emergency Management Support. Beginning in fiscal 2023, the division will include a new centralized Emissions Event Review Program.

HOMELAND SECURITY

The Homeland Security Program coordinates communications during disaster response with federal, state, and local partners; conducts assessments of threats to the state’s critical infrastructure; and participates in the state’s counterterrorism task forces. The program provides agency representation at the State Operations Center during disasters and reviews and provides input on statewide plans coordinated by the Texas Division of Emergency Management and the Texas Department of Public Safety.

DAM SAFETY

The Dam Safety Program monitors and regulates private and public dams in Texas. The program periodically inspects dams that pose a high or significant hazard and issues recommendations and reports to the dam owners to help them maintain safe facilities. The program ensures that these facilities are constructed, maintained, repaired, or removed safely. High- or significant-hazard dams are those for which loss of life could occur if the dam should fail.

Dams are exempted from the program’s regulation if they meet all the following criteria:

- Are privately owned,

- Are classified either “low hazard” or “significant hazard,”

- Have a maximum capacity of less than 500 acre-feet,

- Are within a county with a population of less than 350,000, and

- Are outside city limits.

As of July 29, 2022, a total of 3,228 dams are exempted.

In fiscal 2021, Texas had 4,051 state-regulated dams, including 1,505 high-hazard dams and 305 significant- hazard dams. The remaining dams were classified as low hazard. In fiscal 2022, Texas had 4,106 state-regulated dams, including 1,525 high-hazard dams and 307 significant-hazard dams.

In fiscal 2022, 80% of all high- and significant-hazard dams had been inspected during the past five years. About 978 of the inspected dams are in either “fair” or “poor” condition. After the inspections, many dam owners make repairs if they can identify a funding source.

RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS COMPLIANCE AND CHEMICAL REPORTING

Radioactive Materials Compliance Program

This program focuses on the safety and security of radioactive materials waste in Texas. Investigators conduct radioactive-materials compliance inspections statewide and are members of the state radiological emergency-response team. The investigators are responsible for inspections at regulated facilities including uranium mining or recovery, waste processing or storage, radioactive by-product handling or disposal, low-level radioactive waste disposal, and Underground Injection Control (UIC) permit sites. The following radioactive material license inspections and UIC permit inspections were conducted and approved:

- Fiscal 2021: 10 radioactive material license inspections; 6 UIC permit inspections

- Fiscal 2022: 10 radioactive material license inspections; 2 UIC permit inspections

Texas Compact Waste Facility

The Radioactive Materials Compliance Program is responsible for compliance at the disposal site for low-level radioactive waste in Andrews County. Waste Control Specialists LLC (WCS) operates the Texas Compact Waste Facility under TCEQ-issued Radioactive Material License R04100 and was authorized to accept radioactive waste for disposal in April 2012.

The Radioactive Materials Compliance Program maintains two full-time resident inspectors at the WCS site to inspect and approve the disposal of each waste shipment. The following volume of shipments of low-level radioactive waste was inspected and successfully disposed of in the Texas Compact Waste Facility:

- Fiscal 2021: 190 shipments

- Fiscal 2022: 203 shipments

Tier II Chemical Reporting Program

The Texas Tier II Chemical Reporting Program is the state repository for hazardous-chemical inventories—called Texas Tier II reports—which are required under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act.

Texas Tier II reports contain detailed information on chemicals that meet or exceed specified reporting thresholds at any time during a calendar year. The Tier II reporting system identifies facilities and owner-operators and collects detailed data on hazardous chemicals stored at reporting facilities within the state. The following volume of facility reports was received in the online reporting system:

- Fiscal 2021: 8,307 reports with 80,912 facilities

- Fiscal 2022: 8,849 reports with 87,172 facilities

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

TCEQ’s 16 regional offices form the basis of the agency’s support for local jurisdictions addressing emergency and disaster situations. During a disaster, Disaster-Response Strike Teams (DRSTs), organized in each regional office, serve as TCEQ’s initial and primary responders within their respective regions. Team members come from various disciplines and have been trained in the National Incident Management System, Incident Command System, and TCEQ disaster-response protocols.

TCEQ’s Emergency Management Support Team (EMST), based in Austin, joins the regional DRSTs during disaster responses. The EMST is also responsible for maintaining preparedness, assisting with developing the DRSTs in each region by providing disaster-preparedness training, and maintaining sufficiently trained personnel so that response staff can rotate during long-term emergency events.

The EMST also coordinates the BioWatch program, a federally funded initiative aimed at early detection of bioterrorism agents.

New Emissions Event Review Program

Beginning in fiscal 2023, this new program will investigate all reported emissions in the state. This centralized approach will improve investigative consistency across all regions and industrial sectors and allow for greater efficiency by having staff dedicated to a specific type of investigation. The teams within the section will be divided into specific industry sectors including petrochemical (examples: chemical plants, refineries), oil and gas, and other sources (example: carbon black). The centralized section will also help ensure that there is clear guidance for evaluating affirmative defense claims and an agency-wide approach to provide transparent and consistent evaluations.

ACCREDITED LABORATORIES

TCEQ only accepts regulatory data from laboratories accredited according to standards set by the National Environmental Laboratory Accreditation Program (NELAP) or from laboratories exempt from accreditation, such as a facility’s in-house laboratory.

The analytical data produced by these laboratories are used in TCEQ decisions relating to permits, authorizations, compliance actions, enforcement actions, and corrective actions, as well as in characterizations and assessments of environmental processes or conditions.

All laboratories accredited by TCEQ are held to the same quality-control and quality-assurance standards. TCEQ laboratory accreditations are recognized by other states using NELAP standards and by some states that do not operate accreditation programs of their own.

In fiscal 2022, there were 245 laboratories accredited by TCEQ.

Sugar Land Laboratory

The TCEQ Sugar Land Laboratory is accredited by NELAP. The laboratory:

- Supports monitoring operations for TCEQ’s air, water, and waste programs, as well as river authorities and other environmental partners, by analyzing surface water, wastewater, sediments, sludge samples, and airborne particulate matter for a variety of environmental contaminants.

- Supports the agency by analyzing samples collected as part of investigations conducted by TCEQ’s 16 regional offices.

- Develops analytical procedures and performance measures for accuracy and precision.

- Maintains a highly qualified team of analytical chemists, laboratory technicians, and technical support personnel.

- Generates scientifically valid and legally defensible test results under its NELAP-accredited quality system.

Analytical data are produced using methods approved by EPA. The standards used for these methods are traceable to national standards, from institutions such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the American Type Culture Collection.

With the near-instant transmission of electronic data, TCEQ can now upload results directly to the agency’s Sugar Land Lab database.

EDWARDS AQUIFER PROTECTION PROGRAM

As a karst aquifer, the Edwards Aquifer is one of the most permeable and productive groundwater systems in the U.S. The regulated portion of the aquifer crosses eight counties in south-central Texas, serving as the primary source of drinking water for more than 2 million people in the San Antonio area. This replenishable system also supplies water for farming and ranching, manufacturing, mining, recreation, and the generation of electric power using steam.

The aquifer’s pure spring water also supports a unique ecosystem of aquatic life, including several threatened and endangered species.

Because of the unusual nature of the aquifer’s geology and biology—and its role as a primary water source—TCEQ requires an Edwards Aquifer protection plan for any regulated activity proposed within the recharge, contributing, or transition zones. Regulated activities include construction, clearing, excavation, or anything that alters the surface or possibly contaminates the aquifer and its surface streams. In regulated areas, best management practices for treating stormwater are mandatory during and after construction.

Each year, TCEQ receives hundreds of plans that its Austin and San Antonio regional staff review. TCEQ reviewed 772 plans in fiscal 2021 and 835 plans in fiscal 2022.

In addition to reviewing plans for development within the regulated areas, agency personnel conduct compliance investigations to ensure that best management practices are appropriately used and maintained. Staff also perform site assessments before the start of regulated activities to ensure that aquifer-recharge features are adequately identified for protection.

Air Quality

Changes to Standards for Criteria Pollutants

Federal clean-air standards, or the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), cover six criteria air pollutants: ozone, particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide (SO2). The federal Clean Air Act (FCAA) requires EPA to review the standard for each criteria pollutant every five years to ensure that it achieves the required level of health and environmental protection.

- On March 18, 2019, EPA published its decision to retain the current NAAQS for SO2 without revision, effective April 17, 2019.

- On Dec. 18, 2020, EPA published its decision to retain, without changes, the current NAAQS for PM for both the primary and secondary standards. On June 10, 2021, EPA announced that it will reconsider the December 2020 decision to retain the NAAQS for PM.

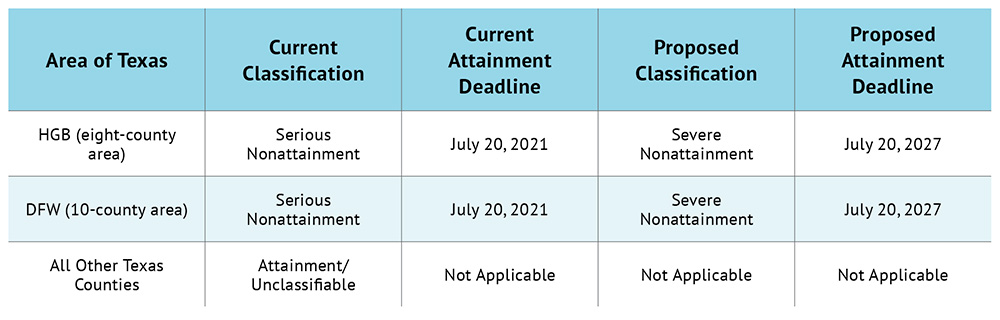

Table 3. Ozone-Compliance Status for the 2008 Eight-Hour Standard

A proposed EPA rule is anticipated in 2022 with a final rule in 2023.

- On Dec. 31, 2020, EPA published its decision to retain the current eight-hour ozone NAAQS. On Oct. 29, 2021, EPA announced that it will reconsider the 2020 decision to retain the current NAAQS for ozone. EPA is targeting the end of 2023 to complete this reconsideration.

- EPA is in the process of reviewing the current NAAQS for lead with a proposed rule anticipated in early 2025 and a final rule in early 2026.

As TCEQ develops plans to address air quality issues, it revises the State Implementation Plan (SIP) and submits these revisions to EPA.

Ozone Standards

2008 OZONE STANDARD

On May 21, 2012, EPA published final designations for the 2008 eight-hour ozone standard of 0.075 parts per million. The Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) area was designated “nonattainment,” with a “moderate” classification, and the Houston-Galveston-Brazoria (HGB) area was designated “nonattainment,” with a “marginal” classification. The HGB area did not attain the 2008 eight-hour ozone standard by its marginal attainment deadline and was reclassified to moderate nonattainment effective Dec. 14, 2016.

The DFW and HGB moderate nonattainment areas were required to attain the 2008 eight-hour ozone standard by July 20, 2018, with a 2017 attainment year, which is the year that the areas were required to measure attainment of the applicable standard. Because neither area attained by the end of 2017, EPA reclassified both the DFW and HGB 2008 eight-hour ozone moderate nonattainment areas to “serious” effective Sept. 23, 2019. The attainment date for serious nonattainment areas was July 20, 2021, with a 2020 attainment year. Serious classification attainment demonstrations and reasonable further progress SIP revisions were developed for both areas and submitted to EPA before the Aug. 3, 2020, deadline. On June 30, 2021, the commission adopted a rulemaking to address the EPA’s Oil and Natural Gas Control Techniques Guidelines in the HGB area.

The DFW and HGB serious nonattainment areas did not attain by the end of 2020; however, the HGB area was eligible for a one-year attainment date extension. On April 6, 2021, TCEQ submitted a one-year attainment date extension request. On April 13, 2022, EPA proposed to reclassify both the DFW and HGB areas to “severe” and deny the HGB area extension request. EPA also proposed TCEQ submit federally required severe classification SIP revisions 18 months after reclassification. Attainment would be required by the end of 2026 to meet a July 20, 2027, attainment date for the DFW and HGB areas.

2015 OZONE STANDARD

Background

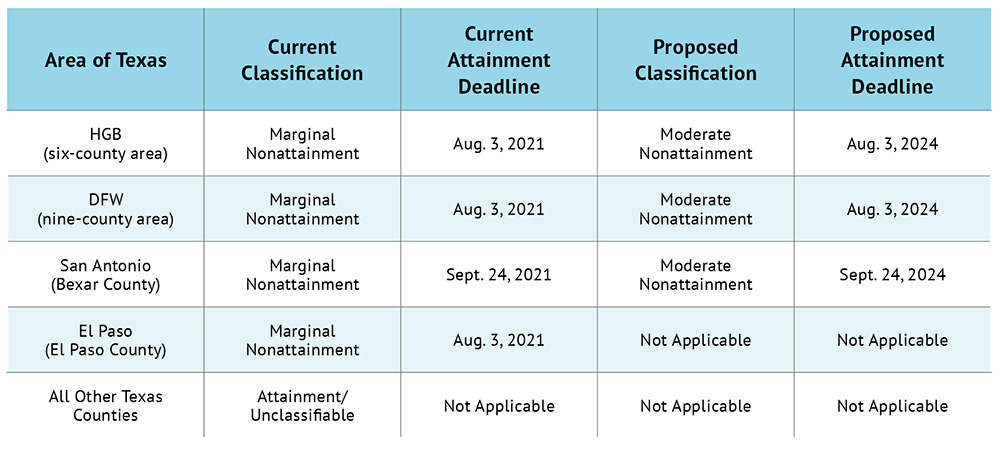

In October 2015, EPA finalized the 2015 eight-hour ozone standard of 0.070 parts per million. On Nov. 16, 2017, EPA designated a majority of Texas as “attainment/unclassifiable” for the 2015 eight-hour ozone NAAQS with an effective date of Jan. 16, 2018. On June 4, 2018, EPA published final designations for the remaining areas, except for the eight counties that compose the San Antonio area. Consistent with state designation recommendations, EPA finalized nonattainment designations for a nine-county DFW marginal nonattainment area and a six-county HGB marginal nonattainment area. EPA designated all the remaining counties, except those in the San Antonio area, as attainment/unclassifiable. The designations were effective Aug. 3, 2018.

San Antonio Area

On July 25, 2018, EPA designated Bexar County as nonattainment, and the seven other San Antonio area counties—Atascosa, Bandera, Comal, Guadalupe, Kendall, Medina, and Wilson—as attainment/unclassifiable, effective Sept. 24, 2018.

In August 2018, the state of Texas and TCEQ sued EPA, challenging EPA’s nonattainment designation for Bexar County in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Environmental petitioners also sued EPA for its designation of attainment/unclassifiable for the seven other San Antonio area counties—Atascosa, Bandera, Comal, Guadalupe, Kendall, Medina, and Wilson. The litigation was consolidated in the 5th Circuit. The court issued its opinion on Dec. 23, 2020, finding that EPA has discretion to make changes it “deems necessary” to the governor’s initial designations and that EPA used a permissible, multi-factor analysis to determine not to add surrounding counties to the Bexar County nonattainment area.

On June 10, 2020, the commission adopted an emissions inventory SIP revision for the 2015 eight-hour ozone NAAQS for the HGB, DFW, and Bexar County nonattainment areas. TCEQ submitted it to EPA on June 24, 2020. EPA published final approval of the emissions inventories for the HGB, DFW, and Bexar County areas on June 29, 2021, and published final approval of the nonattainment new source review and emissions statements portions of the SIP revision on Sept. 9, 2021.

On July 1, 2020, the commission adopted the FCAA, Section 179B, demonstration SIP revision to demonstrate that the Bexar County marginal nonattainment area would attain the 2015 eight-hour ozone standard by its attainment deadline were it not for anthropogenic emissions emanating from outside the U.S. TCEQ submitted it to EPA on July 13, 2020.

DFW, HGB, and San Antonio Area Status

The attainment deadline for the DFW and HGB marginal nonattainment areas was Aug. 3, 2021, which was not met. The attainment deadline for the Bexar County marginal nonattainment area was Sept. 24, 2021, which was not met. On April 13, 2022, EPA proposed to reclassify the DFW, HGB, and Bexar County areas to moderate and disapprove the Bexar County 179B Demonstration SIP Revision. EPA is proposing Jan. 1, 2023, as the deadline for TCEQ to submit federally required moderate classification SIP revisions. Attainment for all three areas would be required by the end of 2023 to meet the attainment dates of Aug. 3, 2024, for the DFW and HGB areas and Sept. 24, 2024, for the Bexar County area.

Table 4. Ozone-Compliance Status for the 2015 Eight-Hour Standard

El Paso Area

In August 2018, the City of Sunland Park, New Mexico, and environmental petitioners challenged EPA’s attainment/unclassifiable designation for El Paso County in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. On July 10, 2020, the court granted EPA’s request for voluntary remand, but did not vacate, the El Paso County attainment designation, requiring EPA to issue a revised El Paso County designation as expeditiously as practicable [Clean Wisconsin v. EPA, 964 F.3d 1145 (D.C. Circuit 2020)]. On Nov. 30, 2021, EPA published a final nonattainment designation for the 2015 ozone NAAQS for El Paso County. EPA expanded the Sunland Park nonattainment area to include all of El Paso County and the area was renamed the “El Paso-Las Cruces, Texas-New Mexico nonattainment area.” El Paso County was classified as marginal nonattainment with a retroactive attainment date of Aug. 3, 2021, and the designation became effective Dec. 30, 2021. A SIP revision to address marginal nonattainment area requirements is due to EPA by Dec. 30, 2022.

On Feb. 28, 2022, TCEQ submitted the FCAA, Section 179B demonstration to EPA for the El Paso County portion of the El Paso–Las Cruces, Texas– New Mexico nonattainment area. The demonstration documented that El Paso County would have attained the 2015 eight-hour ozone NAAQS by the Aug. 3, 2021, attainment date “but for” emissions emanating from outside the U.S. The EPA approval of the 179B demonstration would prevent El Paso County from being reclassified from marginal to moderate nonattainment for the 2015 ozone NAAQS.

On June 15, 2022, the commission approved proposal of the 2015 Eight-Hour Ozone NAAQS emissions inventory SIP Revision for the El Paso County portion of the El Paso–Las Cruces, Texas–New Mexico nonattainment area. The proposed SIP revision satisfies FCAA emission inventory reporting requirements for El Paso County for the 2015 ozone NAAQS and also includes a certification statement to confirm that the emissions statements and nonattainment new source review requirements have been met for El Paso County. Commission adoption of the emissions inventory SIP revision is currently scheduled for Nov. 16, 2022.

Permian Basin

EPA is considering a discretionary redesignation for portions of the Permian Basin in New Mexico and Texas for the 2015 ozone NAAQS based on current monitoring data from New Mexico and other air quality factors. If the area is redesignated to nonattainment, TCEQ will be required to submit a SIP revision to bring the area into attainment. The potential redesignation and the nonattainment area boundaries, still unknown, are expected to cover counties in New Mexico and Texas.

In anticipation of the potential redesignation on June 27, 2022, Gov. Greg Abbott sent a letter to President Joe Biden stating that EPA’s discretionary action would jeopardize oil production in Texas. On July 27, 2022, EPA responded to Gov. Abbott’s letter on behalf of President Biden and indicated that any redesignations from attainment to nonattainment would follow the requirements of FCAA, Section 107(d)(3). Per those requirements, EPA would notify the governor of the redesignation, the affected states would have an opportunity to provide feedback, and EPA would issue a final decision no less than 240 days from the date the agency notifies the governor. On Aug. 23, 2022, Gov. Abbott responded with a letter to the president outlining flaws with EPA’s potential discretionary redesignation, noting the accelerated timing of actions by EPA, and reiterating points from the June 27, 2022, letter.

Transport Rule

In addition to the SIP revisions for areas designated nonattainment for the 2015 ozone standard, TCEQ submitted a transport SIP revision on Aug. 18, 2018, demonstrating that emissions from Texas sources do not contribute significantly to nonattainment or maintenance of the 2015 ozone standard in any other state.

On Feb. 22, 2022, EPA proposed to disapprove Texas’ transport SIP based on its own modeling analysis. On April 6, 2022, EPA proposed to replace Texas’ transport SIP with a Federal Implementation Plan, known as the Transport Rule. The proposed Transport Rule would establish an allowance-based ozone season (May through September) trading program with nitrogen oxide (NOX) emissions budgets for fossil fuel-fired power plants in 25 states, including Texas. The rule would also establish NOX emissions limitations for certain other industrial stationary sources in 23 states, including Texas. The proposed control measures for the identified electric generating unit and non-electric generating unit sources apply to both existing units and any new, modified, or reconstructed units meeting the proposal’s applicability criteria.

On June 21, 2022, TCEQ submitted comments to EPA on the proposed Transport Rule. The comments included a request that EPA approve TCEQ’s 2018 SIP revision and remove Texas from the Transport Rule.

2010 SO2 STANDARD

EPA revised the SO2 NAAQS in June 2010, adding a one-hour primary standard of 75 parts per billion. In July 2013, EPA designated 29 areas in 16 states, which did not include Texas, as nonattainment for the 2010 standard. On March 2, 2015, a U.S. district court order set a deadline for EPA to complete an additional three rounds of designations for the SO2 NAAQS.

Effective Jan. 12, 2017, portions of Freestone and Anderson counties (Big Brown), portions of Rusk and Panola counties (Martin Lake), and a portion of Titus County (Monticello) were designated nonattainment. In October 2017, Luminant (Vistra Energy) filed notices with the Electric Reliability Council of Texas stating its plans to retire the Big Brown and Monticello power generation plants. TCEQ voided permits for these two plants on March 30, 2018.

On Aug. 22, 2019, EPA proposed error corrections to revise the designations of portions of Freestone, Anderson, Rusk, Panola, and Titus counties from nonattainment to unclassifiable; however, the error correction was never finalized. On April 27, 2020, Sierra Club filed suit against EPA, because EPA did not issue findings of failure to submit attainment demonstrations for the three nonattainment areas. EPA published its finding of failure to submit for these three nonattainment areas on Aug. 10, 2020, effective Sept. 9, 2020.

On Feb. 9, 2022, the commission adopted the Rusk-Panola 2010 SO2 NAAQS Attainment Demonstration SIP Revision and associated agreed order to address the finding of failure to submit. TCEQ submitted the SIP revision to EPA on Feb. 28, 2022. On Feb. 23, 2022, the commission adopted the Redesignation Request and Maintenance Plan SIP Revision for the Freestone-Anderson and Titus SO2 NAAQS Nonattainment Areas to request redesignation to attainment and address remaining requirements from the finding of failure to submit. TCEQ submitted the SIP revision to EPA on March 3, 2022.

On March 26, 2021, EPA published nonattainment designations for portions of Howard, Hutchinson, and Navarro counties that were effective April 30, 2021. SIP revisions for the nonattainment areas are due to EPA by Oct. 30, 2022. The commission approved proposed SO2 attainment demonstration SIP revisions for Howard, Hutchinson, and Navarro counties and the associated proposed Title 30, Texas Administrative Code, Chapter 112 rulemaking on April 13, 2022. Commission adoption of the SIP and rule revisions is currently scheduled for Oct. 5, 2022.

Evaluating Health Effects

In a variety of ways, TCEQ toxicologists meet their goals of identifying chemical hazards, evaluating potential exposures, assessing human health risks, and communicating risk to the general public and stakeholders. Perhaps most notably, TCEQ relies on health- and welfare-protective values developed by its toxicologists to ensure that both permitted and monitored airborne concentrations of pollutants stay below levels of concern. So far, TCEQ has derived final toxicity values for 324 pollutants. Numerous federal agencies and academic institutions have recognized Texas for these values and many other states and countries use them.

TCEQ toxicologists use the health- and welfare-protective values they derive—called air monitoring comparison values (AMCVs). AMCVs are used to evaluate the public-health risk of millions of measurements of air pollutant concentrations that are collected from the ambient air monitoring network throughout the year.

When necessary, TCEQ also conducts health-effects research on particular chemicals with limited or conflicting information. In fiscal 2020 and 2021, TCEQ and its contractors completed specific work evaluating associations between particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) and adverse health effects, as well as research to understand health risks in communities with neighboring industrial facilities, such as refineries. This work can inform the review and assessment of state and federal air quality regulations, and the health risks to humans from exposure to air, water, or soil samples collected during investigations and remediation. It can also aid in communicating health risks to the public.

Finally, TCEQ toxicologists communicate risk and toxicology with state and federal legislators and their committees, EPA, other government agencies, the press, and judges during legal proceedings. This often includes input on EPA rulemaking, including the NAAQS, through written comments, meetings, and scientific publications.

Air Pollutant Watch List

TCEQ toxicologists oversee the Air Pollutant Watch List activities that result when ambient pollutant concentrations exceed protective levels. TCEQ routinely reviews and conducts health-effects evaluations of ambient air monitoring data from across the state by comparing air toxic concentrations to their respective AMCVs or state standards. TCEQ evaluates areas for inclusion on the Air Pollutant Watch List where monitored concentrations of air toxics are persistently measured above AMCVs or state standards.

The purpose of the watch list is to reduce air toxic concentrations below levels of concern by focusing TCEQ resources and heightening the awareness of interested parties in areas of concern.

TCEQ also uses the watch list to identify companies with the potential for contributing to elevated ambient air toxic concentrations and then develop strategic actions to reduce emissions. An area’s inclusion on the watch list results in more stringent permitting, priority in investigations, and in some cases, increased monitoring.

Four areas of the state are currently on the watch list. TCEQ continues to evaluate the current and historical Air Pollutant Watch List areas to determine whether improvements in air quality have occurred and are maintained. TCEQ has also identified areas in other parts of the state with monitoring data that are close or slightly above AMCVs, and is working proactively with nearby companies to reduce air toxic concentrations, preventing the need for listing these areas on the watch list.

You can find the Air Pollutant Watch List at www.tceq.texas.gov/toxicology/apwl.

Air Monitoring

TCEQ monitors air quality across the state using a network of stationary air monitors, mobile monitoring assets, and handheld monitors. Ambient air quality monitoring allows the agency to determine compliance with federal air quality standards, evaluate air pollution trends, study air pollution formation and behavior, assess localized air quality concerns, and provide support during environmental emergencies and natural disaster recovery.

While ambient air monitors can measure the impact on air quality from a variety of sources in an area, they are not intended to measure emissions or determine compliance from individual sources or facilities.

STATIONARY MONITORING

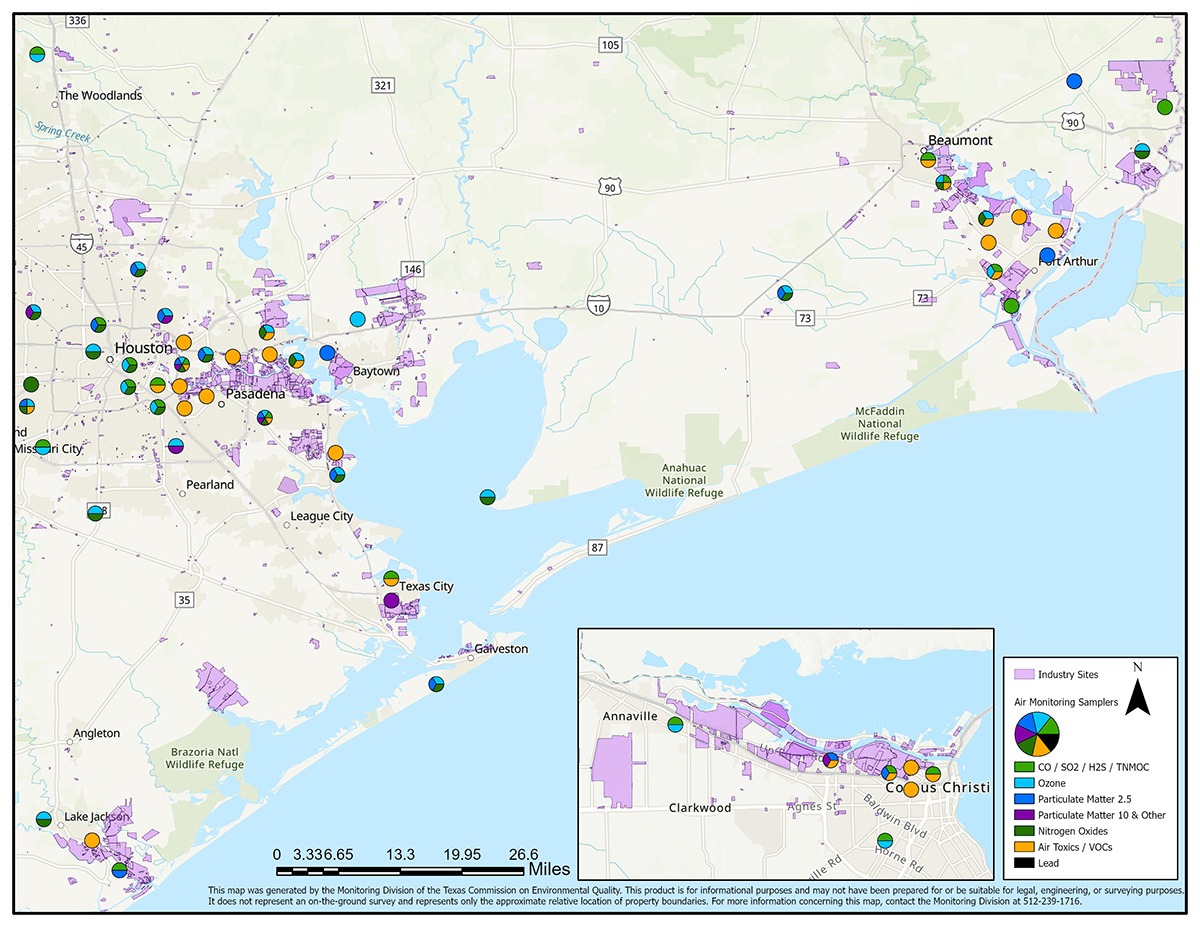

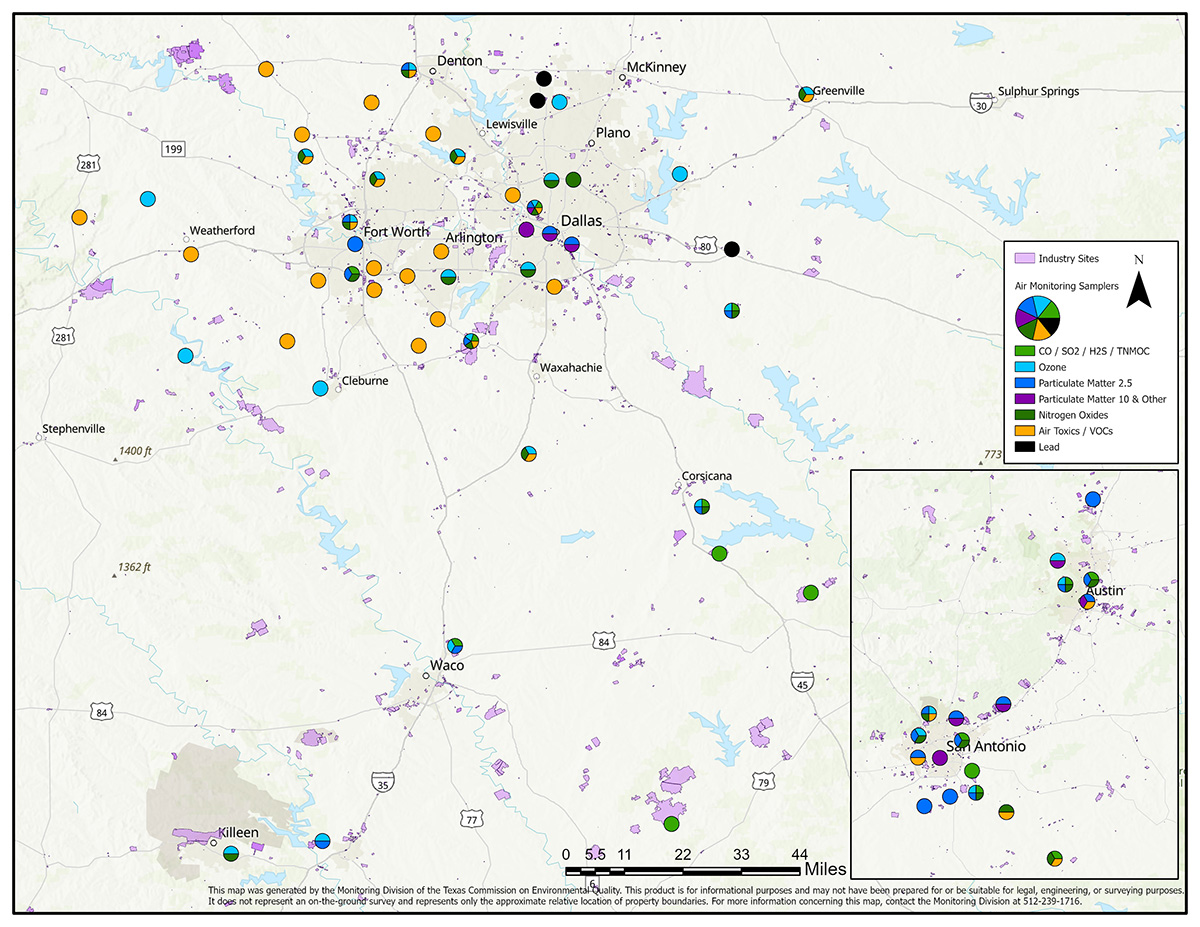

TCEQ’s stationary air monitoring network consists of over 170 monitoring stations serving over 25 million Texans. Designed to meet federal air monitoring requirements, the stationary network includes more than double the number of monitors required by federal rule, in addition to numerous state-initiated ones. As illustrated in figures 1 and 2, monitors are predominantly located in population centers, with increased coverage in metropolitan areas with greater industrial activity.

Figure 1. Coastal Area Air Monitoring Stations

Figure 2. Dallas-Fort Worth and Central Texas Air Monitoring Stations

MONITORING VANS

Augmenting the stationary network are a fleet of three Strategic Mobile Air Reconnaissance Technology (SMART) vans capable of continuous, real-time measurement of a wide range of target pollutants while in transit. These monitoring vans use on-board instruments and GPS mapping to provide:

- net upwind and downwind measurements;

- in-transit surveys to identify pollution hot spots;

- identification of odorous compounds;

- plume tracing using wind speed, wind direction, and optical gas imaging of potential sources; and

- data for assessing regulatory and health impacts.

Housed in Austin, these three monitoring vans can travel anywhere in Texas to conduct short-term, air monitoring assessments in support of regional investigations, special air quality projects, environmental emergencies, and natural disaster recovery.

In addition to the Austin-based SMART vans, TCEQ’s Beaumont, Houston, and Corpus Christi regions each house a rapid assessment survey vehicle capable of continuous, real-time measurement and mapping of fourteen target compounds. Expanding on this concept, TCEQ will also deploy additional rapid assessment survey vehicles in its Dallas-Fort Worth and Midland-Odessa regions in fiscal 2023.

HANDHELD MONITORING

Handheld air monitoring equipment and optical gas imaging cameras allow TCEQ to assess air quality at the source level in response to complaints, environmental emergencies, and natural disasters. Using these tools, investigators routinely conduct air reconnaissance to identify potential sources impacting air quality for further evaluation and enforcement. They target areas of concern, such as the Gulf Coast’s industrial ports and near oil and gas refineries.

Methane Rule for Crude Oil and Natural Gas Sources

On Nov. 15, 2021, EPA published the proposed New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) under FCAA Subsection 111(b). The proposed rulemaking would update, strengthen, and expand the current NSPS for methane and volatile organic compounds emitted from crude oil and natural gas sources that had begun construction, modification, or reconstruction after Nov. 15, 2021, and includes standards for emission sources not previously regulated.

Also, on Nov. 15, 2021, EPA published the proposed emissions guidelines under FCAA Subsection 111(d) for the crude oil and natural gas sector, including the production, processing, transmission, and storage segments. The proposed rulemaking would establish emissions guidelines for states to use in developing, submitting, and implementing state plans that are required to establish standards of performance for methane emissions from crude oil and natural gas sources existing as of Nov. 15, 2021.

EPA is expected to issue a supplemental rulemaking proposal in October 2022 that will provide regulatory text and may expand on or modify these requirements for NSPS and emissions guidelines in response to public input. The final rule is expected May 2023.

Regional Haze

Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend national parks are identified by the federal government for visibility protection, along with 154 other national parks and wilderness areas. Regional Haze is a long-term air quality program requiring states to develop plans to meet a goal of natural visibility conditions by 2064. In Texas, the primary visibility-impairing pollutants are NOX, SO2, and PM. Requirements for the Regional Haze Program include a Regional Haze SIP revision that is due to EPA every 10 years and a progress report due every five years, to demonstrate progress toward natural conditions.

The first Texas Regional Haze SIP revision was submitted to EPA in 2009. In 2016, EPA finalized a partial disapproval of that plan and proposed a Federal Implementation Plan (FIP) that would have required emissions control upgrades or emissions limits at eight coal-fired power plants in Texas. In July 2016, Texas and other petitioners challenged the FIP action in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, contending that EPA acted outside its statutory authority. In 2017, EPA asked the court to remand the FIP back to EPA and sought a stay of the litigation pending review of the FIP, which was granted by the court. In July 2022, the court directed EPA to issue a status report with a timeline with specific dates for when the agency will complete the voluntary remand. EPA’s July 15, 2022, status report indicated that it will complete action on the remand by Dec. 31, 2023.

Due to continuing issues with the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR), EPA could not act on best available retrofit technology (BART) requirements for electric generating units (EGUs). On March 20, 2018, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling upholding “CSAPR-better-than-BART” for regional haze.

On Oct. 17, 2017, EPA adopted a FIP to address BART for EGUs in Texas, which included an alternative trading program for SO2. EPA will administer the trading program, which includes only specific EGUs in Texas and no out-of-state trading. For NOX, Texas remains in CSAPR. For PM, EPA determined that no further action was required. On June 29, 2020, EPA finalized the amended BART intrastate trading program FIP for Texas, and the trading program was affirmed as an alternative to BART requirements for certain sources in Texas.

TCEQ submitted Texas’ Regional Haze SIP revision for the second planning period to EPA on July 20, 2021, before the July 31, 2021, deadline. The analyses performed for the SIP revision found that the estimated annualized costs of implementing additional controls for the second planning period would be approximately $200 million and would result in visibility benefits that would be imperceptible to the human eye. Therefore, the commission found that additional emissions controls are unreasonable for the second planning period. This SIP revision is under EPA review.

Major Incentive Programs

TEXAS EMISSIONS REDUCTION PLAN

TCEQ’s Texas Emissions Reduction Plan (TERP) provides grants to individuals and entities for projects that will lower NOX emissions from mobile sources.

Because NOX is a leading contributor to the formation of ground-level ozone, reducing these emissions is key to complying with the federal ozone standard. Programs under TERP also:

- Encourage using natural gas vehicles and other alternative fuel vehicles, and installing infrastructure to provide fuel for those vehicles.

- Reduce emissions of diesel exhaust from school buses.

- Advance technologies that reduce NOX and other emissions from facilities and other stationary sources.

- Conduct studies and fund pilot programs that encourage port authorities to reduce emissions caused by moving cargo.

The ten TERP programs are listed on page 26. TCEQ expects to continue to award funds under each of these programs during fiscal 2023.

Diesel Emissions Reduction Incentive (DERI) Program

- Upgrades or replaces heavy-duty vehicles, locomotives, marine vessels, or other pieces of equipment in nonattainment areas and affected counties with newer, cleaner models.

- Over $1 billion awarded from 2001 through August 2021 to upgrade or replace 20,472 vehicles, locomotives, vessels, and equipment.

- Projected to reduce NOX emissions by 189,242 tons in the nonattainment areas and other affected counties.

Seaport and Rail Yard Areas Emissions Reduction (SPRY) Program

- Repowers or replaces older drayage trucks and equipment operating at eligible seaports and rail yards in nonattainment areas with newer, cleaner models.

- Over $28 million awarded from 2015 through August 2022 to replace 343 vehicles and pieces of equipment.

- Projected to reduce NOX by 952 tons in the nonattainment areas and other affected counties.

Port Authority Studies and Pilot Programs (PASPP)

- Provides grants to port authorities located in the nonattainment areas or affected counties. They use the funds to conduct studies and implement pilot programs to reduce emissions of NOX and PM caused by moving cargo.

- $2 million awarded from 2018 through August 2021 for two studies and pilot programs.

Texas Clean Fleet Program (TCFP)

- Assists owners of large fleets in Texas with replacing diesel-powered vehicles with new alternative fuel or hybrid vehicles

- Over $69 million awarded from 2009 through August 2021 to replace 730 vehicles.

- Projected to reduce NOX emissions in the counties of the Clean Transportation Zone by 699 tons.

Texas Natural Gas Vehicle Grants Program (TNGVGP)

- Replaces or repowers diesel- or gasoline-powered vehicles with new or used natural gas vehicles or new natural gas engines.

- Over $54 million awarded from 2009 through August 2021 to replace or repower 1,148 vehicles.

- Projected to reduce NOX emissions in the counties of the Clean Transportation Zone by 1,674 tons.

Alternative Fueling Facilities Program (AFFP)

- Helps to ensure that alternative fuel vehicles have access to fuel and builds the foundation for a self-sustaining market for alternative fuels in Texas.

- Over $31 million awarded from 2012 through August 2021 for constructing or expanding 311 alternative fueling facilities, including 102 natural gas fueling facilities, 182 electric charging stations, and 27 fueling facilities for other alternative fuels.

Texas Clean School Bus (TCSB) Program

- Reduces the exposure of children across Texas to diesel exhaust in and around school buses by replacing or retrofitting older school buses.

- Over $48 million awarded from 2008 through August 2022, including over $4 million in federal funds, to retrofit or replace 7,857 buses.

New Technology Implementation Grant (NTIG) Program

- Reduces emissions from facilities and other stationary sources.

- Over $16 million awarded from 2010 through August 2021 for 10 projects.

Light-Duty Motor Vehicle Purchase or Lease Incentive Program (LDPLIP)

- Supports purchases of light-duty vehicles operating on natural gas, propane, or electricity.

- Over $15 million awarded from 2014 through August 2022 for purchasing or leasing 6,574 vehicles, including 6,309 rebates for plug-in electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, and 265 rebates for natural gas vehicles.

Governmental Alternative Fuel Fleet (GAFF) Program

- Supports state agencies and political subdivisions across Texas in upgrading, replacing, or expanding their vehicle fleets to alternative fuel, and purchasing, leasing, or installing refueling infrastructure for those vehicles.

The TERP Biennial Report to the Texas Legislature (TCEQ publication SFR-079/20) provides further details on the program’s grants and activities.

TEXAS VOLKSWAGEN ENVIRONMENTAL MITIGATION PROGRAM

In December 2017, Gov. Greg Abbott selected TCEQ as the lead agency responsible for administering funds received from the Volkswagen State Environmental Mitigation Trust. A minimum of $209 million dollars will be made available for projects that mitigate the additional NOX emissions from vehicles using defective devices to pass emissions tests.

From 2019 through August 2022, TCEQ awarded over $80 million under the Texas Volkswagen Environmental Mitigation Program for replacing 1,265 vehicles including school buses, transit buses, refuse trucks, local delivery vehicles, and port drayage vehicles. Replacing these vehicles is projected to reduce NOX emissions in the nonattainment areas and other affected counties by 1,471 tons. TCEQ also awarded over $31 million for purchasing and installing 635 electric vehicle charging units.

TCEQ expects to award additional funds under the program in fiscal 2023.

Environmental Research and Development

TCEQ supports scientific research to study air quality in Texas. The Air Quality Research Program (AQRP) is administered by The University of Texas at Austin and funded by TCEQ. AQRP funds projects that build on research from the previous biennium.

AQRP and TCEQ sponsored ship-based ozone and meteorological measurements in Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico to improve the understanding of coastal air quality. The collected data will assess the importance of offshore emission sources and the role of meteorological transport patterns on air quality in the Houston area.

Other important air quality research carried out through AQRP has included the following:

- Projects that examine the impact of biomass burning and wind-blown agricultural dust on air quality in Texas, including fires outside Texas and the U.S.

- Measuring atmospheric chemistry and meteorology from the coastal area of Corpus Christi inland to San Antonio.

- Evaluating satellite data to potentially improve emission inventories.

In addition to research carried out through the AQRP, TCEQ used grants and contracts to support ongoing air quality research. Notable projects have included:

- Supporting the Tracking Aerosol Convection Experiment – Air Quality field campaign in Houston to study ozone formation, evaluate models, and verify emission inventories.

- Analyses of fire impacts on Texas air quality using different modeling and measurement methods, with an emphasis on identifying exceptional events that may affect air quality.

- Updating inventories for emissions from commercial marine vessels, aircraft, locomotives, rail yards, and compressor engines.

- Improving the chemical and meteorological processes of the ozone modeling system.

- Assisting with sulfur dioxide modeling for attainment demonstrations.

- Monitoring studies in El Paso to understand contributions to various pollutants from within and outside the U.S.

The latest findings from these research projects help the state understand and appropriately address some of the challenging air quality issues faced by Texans.

These challenges are increasing—in part due to changes in air quality standards—and addressing them will require continued research. This knowledge helps ensure that Texas adopts attainment strategies that are achievable, sound, and based on the most current information.

Water Quality

Developing Surface Water Quality Standards

TEXAS SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS

Under the federal Clean Water Act, every three years TCEQ is required to review and, if appropriate, revise the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards. These standards are the basis for establishing discharge limits in wastewater permits, setting instream water quality goals for total maximum daily loads, and establishing criteria to assess instream attainment of water quality.

Water quality standards are set for major streams and rivers, reservoirs, and estuaries based on their specific uses: aquatic life, recreation, drinking water, fish consumption, and general. The standards establish water quality criteria for temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, salts, bacterial indicators for recreational suitability, and a number of toxic substances.

Major revisions to water quality standards for 2022 will include:

- Revisions to statewide toxic criteria to incorporate new data on toxicity effects and address revised EPA procedures.

- Revisions and additions to site-specific toxic criteria to incorporate local water quality data into criteria for select water bodies.

- Revisions and additions to the uses, criteria, and descriptions of individual water bodies based on new data and results of recent use attainability analyses (UAAs).

- Additions of site-specific recreational uses for select water bodies based on the results of recent recreational UAAs.

EPA must approve the revised standards before they can be applied to activities related to the federal Clean Water Act. Although federal review of portions of the 2010, 2014, and 2018 standards has yet to be completed, TCEQ completed the 2021 triennial standards review and the 2022 rule revisions are anticipated to be approved in September 2022.

USE-ATTAINABILITY ANALYSES

The Surface Water Quality Standards Program also coordinates and conducts use-attainability analyses to develop site-specific uses for aquatic life and recreation. The UAA assessment is often used to re-evaluate designated or presumed uses when the existing standards may need to be revised for a water body. As a result of aquatic-life UAAs, site-specific aquatic-life uses and dissolved-oxygen criteria are expected to be adopted in the 2022 revision of the standards for individual water bodies.

In 2009, TCEQ developed recreational UAA procedures to evaluate and more accurately assign levels of protection for water recreational activities such as swimming and fishing. Since then, the agency has initiated more than 156 UAAs to evaluate recreational uses of water bodies that have not attained their existing criteria. Using results from recreational UAAs, TCEQ will include site-specific contact recreation criteria for select individual water bodies in the 2022 Texas Surface Water Quality Standards revision.

Also see major revisions to water quality standards above.

Monitoring Water Quality

Surface water quality is monitored across the state in relation to human-health concerns, ecological conditions, and designated uses. The resulting data form a basis for policies that promote the protection and restoration of surface water in Texas. Special projects contribute water quality monitoring data and information on the condition of biological communities. This provides a basis for developing and refining criteria and metrics used to assess the condition of aquatic resources.

CLEAN RIVERS PROGRAM

The Clean Rivers Program administers and implements a statewide framework set out in Texas Water Code, Section 26.0135. This state program works with 15 regional partners (river authorities and others) to collect water quality samples, derive quality-assured data, evaluate water quality issues, and provide a public forum for prioritizing water quality issues in each Texas river basin. This program provides 60 to 75% of the data available in the state’s surface water quality database used for water-resource decisions, including revising water quality criteria, identifying the status of water quality, and supporting the development of projects to improve water quality.

COORDINATED ROUTINE MONITORING

Each spring, TCEQ staff meets with various water quality organizations to coordinate monitoring efforts for the upcoming fiscal year. TCEQ prepares the guidance and reference materials, and the Texas Clean Rivers Program partners coordinate the local meetings. Participants use the available information to select stations and parameters that will enhance the overall coverage of water quality monitoring, eliminate duplication of effort, and address basin priorities.

The coordinated monitoring network, which consists of about 2,000 active stations, is one of the most extensive in the country. Coordinating the monitoring among the various participants ensures that available resources are used as efficiently as possible.

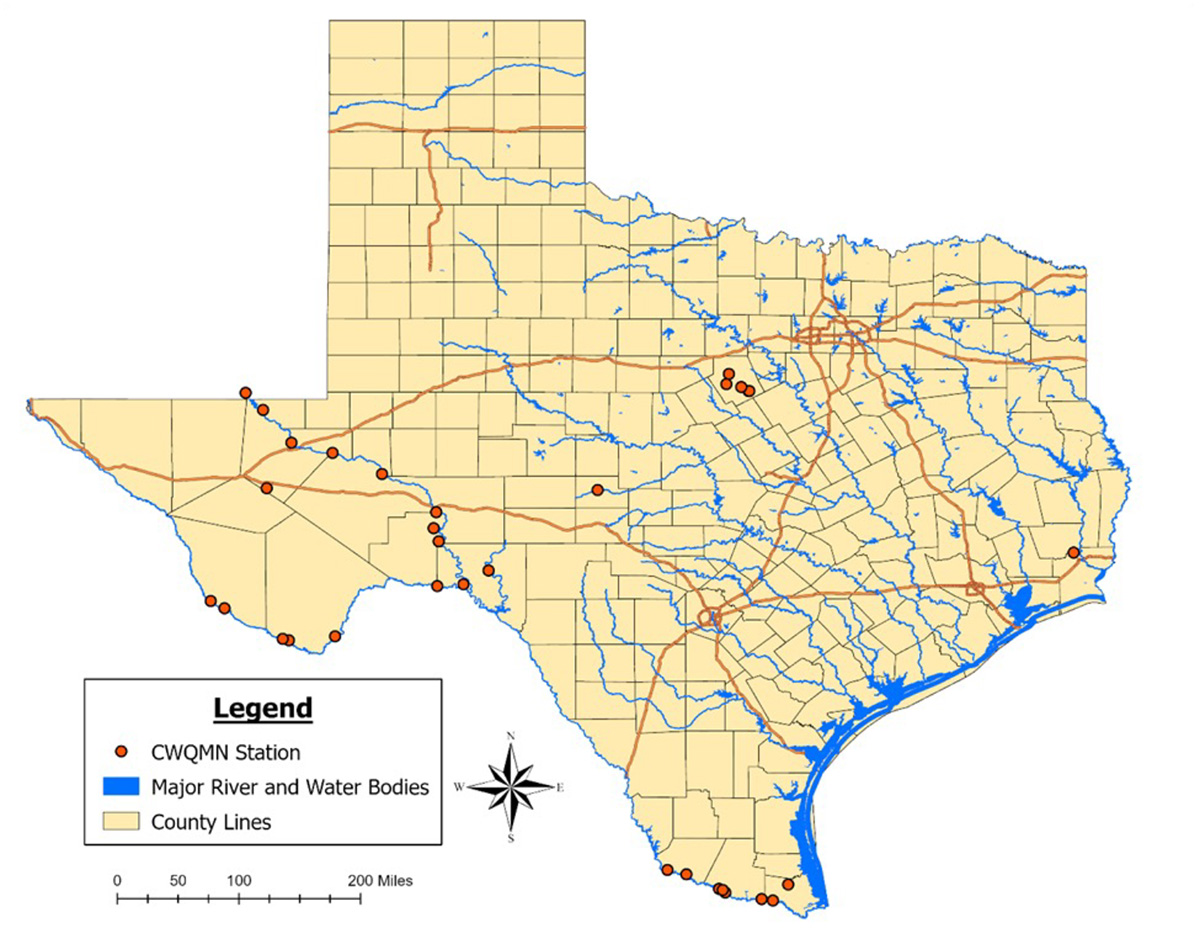

CONTINUOUS WATER QUALITY MONITORING

TCEQ has developed—and continues to refine—a network of continuous water quality monitoring sites on priority water bodies. The agency maintains 30 to 40 sites in its Continuous Water Quality Monitoring Network (CWQMN). At these sites, instruments measure basic water quality conditions every 15 minutes.

TCEQ and other organizations may use CWQMN monitoring data to make decisions about water-resource management to target field investigations, evaluate the effectiveness of water quality management programs such as TMDL implementation plans and watershed protection plans, characterize existing conditions, develop and calibrate water quality models, define stream segment boundaries, and evaluate spatial and temporal trends. The data are posted on TCEQ’s website.

The CWQMN data is used to guide decisions on how to better protect certain segments of rivers or lakes. For example, TCEQ developed a network of 15 CWQMN sites on the Rio Grande and the Pecos River, primarily to monitor levels of dissolved salts to protect the water supply in Amistad Reservoir. The Pecos River CWQMN stations also supply information on the effectiveness of the Pecos River Watershed Protection Plan. The U.S. Geological Survey operates and maintains these stations through cooperative agreements with TCEQ.

Assessing Water Quality

Every even-numbered year, TCEQ assesses water quality to determine which water bodies meet the surface water quality standards for their designated uses, such as contact recreation, support of aquatic life, or drinking-water supply. Data associated with 200 different water quality parameters are reviewed to conduct the assessment. These parameters include physical and chemical constituents, as well as measures of biological integrity.

The assessment is published on TCEQ’s website and submitted as a draft to EPA as the Texas Integrated Report for Clean Water Act Sections 305(b) and 303(d) found at www.tceq.texas.gov/waterquality/assessment.

The Integrated Report evaluates conditions during the assessment period and identifies the status of the state’s surface waters in relation to the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards. Waters that do not regularly attain one or more of the standards may require action by TCEQ and are placed on the 303(d) List of Impaired Water Bodies for Texas (part of the report). EPA must approve this list before its implementation by TCEQ’s water quality management programs.

Because of its large number of river miles, Texas can monitor only a portion of its surface water bodies. The major river segments and those considered at highest risk for pollution are monitored and assessed regularly. EPA approved the 2022 Integrated Report in July of that year. In developing the report, water quality data was evaluated from 2,409 sites on 1,601 water bodies. The draft 2024 Integrated Report is under development.

Restoring Water Quality

WATERSHED ACTION PLANNING

Water quality planning programs in Texas have responded to the challenges of maintaining and improving water quality by developing strategies to address water quality issues in the state. Watershed Action Planning (WAP) is a process for coordinating, documenting, and tracking the actions necessary to protect and improve the quality of the state’s streams, lakes, and estuaries. The major objectives are to:

- Fully engage stakeholders to determine the most appropriate action to protect or restore water quality.

- Improve access to state agencies’ decisions about water quality management and increase the transparency of that decision-making.

- Improve the accountability of state agencies responsible for protecting and improving water quality.

TCEQ, the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board (TSSWCB), and the Texas Clean Rivers Program partners lead the WAP process. Involving stakeholders, especially at the watershed level, is key to the success of the process.

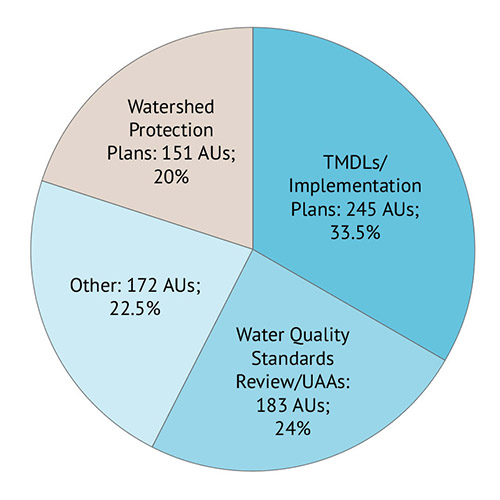

Water impairments can be addressed in a variety of ways. The selection of an appropriate restoration strategy is coordinated with stakeholders through the WAP process. Figure 4 reflects the 2020 Texas Integrated Report. TCEQ is currently in the process of evaluating strategies following EPA’s approval of the 2022 Texas Integrated Report.

Figure 4. Management Strategies for Restoring Water Quality

Total AUs with an assigned restoration strategy: 705

• Watershed Protection Plans, 145 AUs, 20%• Water Quality Standards Review/UAAs, 162 AUs, 23%

• TMDLs/Implementation Plans, 245 AUs, 35%

• Monitoring, 153 AUs, 22%

Source: WAP database and the 2020 Texas Integrated Report

TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD PROGRAM

The TMDL Program is one of the agency’s mechanisms for improving the quality of impaired surface waters. A TMDL is the total amount (or load) of a single pollutant that a receiving water body can assimilate within a 24-hour period and still maintain water quality standards. A rigorous scientific process is used to arrive at practicable targets for the pollutant reductions in TMDLs.

This program works with the agency’s water quality programs, other governmental agencies, and watershed stakeholders during the development of TMDLs and related implementation plans.

Bacteria TMDLs

Bacteria from human and animal wastes can indicate the presence of disease-causing microorganisms that pose a threat to public health. People who swim or wade in waterways with high concentrations of bacteria have an increased risk of contracting gastrointestinal illnesses. High bacteria concentrations can also affect the safety of oyster harvesting and consumption.

Of the 1,051 AUs listed in the 2022 Texas Integrated Report of Surface Water Quality, about one-third are for bacterial impairments to recreational water uses.

The TMDL Program has developed an effective strategy for developing TMDLs that protect recreational safety. The strategy relies on the engagement and consensus of the communities in the affected watersheds. Other actions are also taken to address bacteria impairments, such as recreational use–attainability analyses that ensure that the appropriate contact-recreation use is in place, as well as watershed-protection plans developed by stakeholders and primarily directed at nonpoint sources.

Implementation Plans

While a TMDL analysis is being completed, stakeholders are engaged in the development of an Implementation Plan (I-Plan), which identifies the steps necessary to improve water quality. These I-Plans outline five to ten years of activities, indicating who will carry them out, when they will be done, and how improvement will be gauged. The time frames for completing I-Plans are affected by stakeholder resources and when stakeholders reach consensus. Each plan contains the stakeholders’ commitment to meet periodically to review progress. The plan is revised to maintain sustainability and to adjust to changing conditions.

Programmatic and Environmental Success

Since 1998, TCEQ has been developing TMDLs to improve the quality of impaired water bodies on the federal 303(d) List, which identifies surface waters that do not meet one or more quality standards. In all, the agency has adopted 410 TMDLs for 300 AUs in the state.

From July 2020 to July 2022, the commission adopted 36 TMDLs to address instances where bacteria, dissolved oxygen, or pH had impaired the use of the water bodies. The TMDLs developed and the number of AUs covered were: Carancahua Bay (1); Adams Bayou, Cow Bayou, and Tributaries (23); Walnut Creek (1); Harris County Flood Control Ditch D-138 (1); Horsepen Creek (1); Corpus Christi Bay Beaches (2); Caney Creek (2); Arenosa Creek (1); Hillebrandt Bayou (1); Lavaca River (1); and Sandy Creek and Wolf Creek (2). During that time, the commission also approved two I-Plans—for Carancahua Bay and Arenosa Creek.

The Greater Trinity River Bacteria TMDL I-Plan is an example of successful community engagement to address bacteria impairments. Stakeholders drove the process – with active public participation – to develop the I-Plan. A broad spectrum of authorities and interests took part, including government, agriculture, business, conservation groups, and the general public. The I-Plan identifies nine strategies for activities that address five TMDL projects. Seven AUs in the I-Plan are now meeting their contact recreation uses in the 2022 Integrated Report.

NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM

The Nonpoint Source (NPS) Program administers the provisions of Section 319 of the federal Clean Water Act. Section 319 authorizes grant funding for states to develop projects and implement NPS pollution management strategies to maintain and improve water quality conditions.

TCEQ, in coordination with TSSWCB, manages NPS grants to carry out the long- and short-term goals identified in the Texas NPS Management Program. The NPS Program’s annual report documents progress in meeting these goals.

The NPS grant from EPA is split between TCEQ (to address urban and non-agricultural NPS pollution) and TSSWCB (to address agricultural and silvicultural NPS pollution). TCEQ receives $3 to $4 million annually. About 60% of overall project costs are federally reimbursable; the remaining 40% comes from state or local matching. In fiscal 2022, TCEQ received $3.9 million, which was matched with $2.7 million, for a total of $6.6 million.

TCEQ annually solicits applications to develop projects that contribute to the Texas NPS Management Program. Typically, the program receives, reviews, and scores 20 to 30 applications each year. Because the number of projects funded depends on the amount of each contract, the number of contracts awarded fluctuates. Ten projects were funded in fiscal 2021, and 10 in fiscal 2022. Half of the federal funds awarded must be used to implement watershed-based plans, comprising activities that include public outreach and education, low-impact development, constructing and implementing best management practices, and inspecting and replacing on-site septic systems.

The NPS Program also administers provisions of Section 604(b) of the federal Clean Water Act. These funds are derived from State Revolving Fund appropriations under Title VI of the act. Using a legislatively mandated formula, money is passed through to councils of governments for water quality planning. The program received $734,000 in funding from EPA in fiscal 2021 and $734,000 in fiscal 2022.

Bay and Estuary Programs

The estuary programs are non-regulatory, community-based programs focused on conserving the sustainable use of bays and estuaries in the Houston-Galveston and Coastal Bend bays regions through implementation of comprehensive conservation management plans that are developed locally. Plans for Galveston Bay and the Coastal Bend bays were established in the 1990s and updated in 2019 and 2020, respectively, by a broad-based group of stakeholders and bay user groups. These plans strive to balance the economic and human needs of the regions.

Two different organizations execute the plans: the Galveston Bay Estuary Program (GBEP), which is a program of TCEQ, and the Coastal Bend Bays and Estuaries Program (CBBEP), which is a nonprofit authority established for that purpose. TCEQ partially funds the CBBEP.

Additional coastal activities at TCEQ include:

- Participating in the Gulf of Mexico Alliance, a partnership linking Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. TCEQ contributes staff time to implement the Alliance’s Governors’ Action Plan, focusing on water resources and improved coordination among the states.

- Serving on the Coastal Coordination Advisory Committee and participating in the state’s Coastal Management Program to improve the management of the area’s natural resources and to ensure long-term ecological and economic productivity of the coast.

- Working with the General Land Office to carry out the federally approved Coastal Nonpoint Source Program, which is required under the Coastal Zone Act Reauthorization Amendments.

GALVESTON BAY ESTUARY PROGRAM

GBEP provides ecosystem-based management that strives to balance economic and human needs with available natural resources in Galveston Bay and its watershed. Toward this goal, the program fosters cross-jurisdictional coordination among federal, state, and local agencies and groups, and cultivates diverse public-private partnerships to implement projects and build public stewardship.

GBEP priorities include:

- coastal habitat conservation

- public awareness and stewardship

- water conservation

- nonpoint and point source abatement

- monitoring and research

During fiscal 2021 and 2022, GBEP worked with partners to conduct ecosystem-based monitoring and research to inform resource managers and fill data gaps. The program collaborated with local stakeholders to create watershed-protection plans and carry out water quality projects. They launched the first web-based format of the State of the Bay report, which summarizes monitoring data, research findings, management actions, and historical resource uses—and developed the interactive Regional Monitoring Database where users can view, explore, and download management and research data on Galveston Bay. GBEP also developed an Implementation Tracking Viewer, to track projects by the program and its partners.

In fiscal 2021 and 2022, 6,103.5 acres of coastal wetlands and other important habitats were protected, restored, and enhanced. An additional 820 acres will be placed under conservation by the end of calendar 2022. Since 2000, GBEP and its partners have protected, restored, and enhanced a total of 39,996.49 acres of important coastal habitats.

Through collaborative partnerships established by the program, approximately $7.22 in private, local, and federal contributions was leveraged for every $1 the state dedicated to the program in fiscal 2021 and 2022.

COASTAL BEND BAYS AND ESTUARIES PROGRAM

During fiscal 2021 and 2022, CBBEP implemented 84 projects, including habitat restoration and protection, outreach and educational programs, and studies that promote bay and estuary watershed planning. Based in the Corpus Christi area, CBBEP is a voluntary partnership that works with industry, environmental groups, bay users, local governments, and resource managers to improve the health of the bay system. In addition to receiving program funds from local governments, private industry, TCEQ, and EPA, CBBEP seeks funding from private grants and other governmental agencies. In the last two years, CBBEP secured $17,699,788 in additional funds to leverage TCEQ funding.

CBBEP priority issues focus on human uses of natural resources, freshwater inflows, maritime commerce, habitat loss, water and sediment quality, and education and outreach. One of CBBEP’s goals under their comprehensive conservation and management plan is to address 303(d)-listed segments so that they meet state water quality standards.

Other areas of focus:

- Conserving and protecting wetlands and wildlife habitat through partnerships with private landowners.

- Restoring the Nueces River Delta for the benefit of fisheries, wildlife habitat, and freshwater conservation.

- Environmental education and awareness for more than 7,900 students and teachers annually at the CBBEP Nueces Delta Preserve by delivering educational experiences and learning through discovery and scientific activities.

- Enhancing colonial-waterbird rookery islands by implementing predator control, habitat management, and other actions to help stem the drop in populations of nesting coastal birds in the Coastal Bend and the Lower Laguna Madre.

- Supporting the efforts of the San Antonio Bay Partnership to better characterize the San Antonio Bay system and to develop and implement management plans that protect and restore wetlands and wildlife habitats.

Wastewater Permitting

The Texas Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (TPDES) Program issues site-specific permits to discharge wastewater or stormwater into water in the state. These permits include effluent limitations that ensure that the discharge doesn’t degrade water quality in the receiving stream. There are two types of permits: an individual permit is tailored to an individual facility, whereas a general permit covers a group of dischargers with similar qualities within a given geographic location.

INDUSTRIAL AND MUNICIPAL INDIVIDUAL PERMITS

Industrial wastewater permits are issued for the discharge of wastewater generated from industrial activities. TCEQ issued 121 industrial wastewater permits in fiscal 2021 and 127 in fiscal 2022. Municipal wastewater permits are issued for the discharge of wastewater generated from municipal and domestic activities. TCEQ issued 373 municipal wastewater permits in fiscal 2021 and 530 in fiscal 2022. TCEQ has 23 active individual permits for municipal stormwater.

GENERAL PERMITS

General permits provide a streamlined authorization process for certain discharges of wastewater or stormwater. TCEQ has developed 15 general permits. Applications for stormwater general permits make up a significant portion of the general permit workload. The agency has developed an online application for all stormwater general permits and some of the wastewater general permits to accommodate the growing workload.

STORMWATER PERMITS

TCEQ has three general permits for stormwater based on the source of the stormwater: industrial facilities, construction activities, and municipal entities. The multi-sector general permit regulates stormwater discharges from industrial facilities. The construction general permit regulates stormwater runoff associated with construction activities. The municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) general permit authorizes 515 entities.

Drinking Water Systems

The TCEQ Public Drinking Water Program is responsible for ensuring that Texas citizens receive a safe and adequate supply of drinking water and carries out this responsibility by implementing the Safe Drinking Water Act. All public water systems must be approved by TCEQ prior to beginning operations, provide documentation to show that they meet state and federal requirements, and evaluate the quality of the drinking water

Ensuring Safe Drinking Water

Of the approximate 7,100 public water systems (PWSs) in Texas, about 4,640 are community systems, mostly operated by cities. These systems serve about 97% of Texans. The rest are non-community systems—such as those at schools, churches, factories, businesses, and state parks.

TCEQ offers online data tools so that the public can find information on the quality of locally produced drinking water. Texas Drinking Water Watch (www. tceq.texas.gov/goto/dww) houses analytical results from the compliance sampling of PWSs. The Source Water Assessment Viewer (www.tceq.texas.gov/gis/swaview) shows the location of the sources of drinking water and any potential sources of contamination, such as an underground storage tank.

All PWSs must monitor the levels of contaminants present in treated water and verify that each contaminant does not exceed its maximum contaminant level, action level, or maximum residual disinfection level—the highest level at which a contaminant is considered acceptable in drinking water for the protection of public health.

In all, state and federal regulations have set standards for 102 contaminants in the major categories of microorganisms, disinfection by-products, disinfectants, organic and inorganic chemicals, and radionuclides. TCEQ evaluates approximately 165,000 analytical results each month to determine compliance with these standards. The most significant microorganism is coliform bacteria, particularly E. Coli. The most common chemicals of concern in Texas are disinfection by-products, arsenic, fluoride, and nitrate. TCEQ collects more than 59,981 water samples each year just for chemical compliance. TCEQ contractors collect most of the chemical samples and submit them to an accredited laboratory for analysis. The analytical results are sent to TCEQ and the PWSs.

Each year, TCEQ holds a free symposium on public drinking water, which typically draws more than 1,000 participants. The agency also provides technical assistance to PWSs to ensure that consumer confidence reports are developed correctly and include all required information.

ASSISTING PWSs

TCEQ strives to ensure that all water and wastewater systems have the capability to operate successfully. TCEQ contracts with the Texas Rural Water Association to assist utilities with financial, managerial, and technical expertise. About 1,009 assignments were made through this contract in fiscal 2021, and 1,076 assignments in fiscal 2022.

REVIEWING ENGINEERING PLANS AND SPECIFICATIONS

PWSs are required to submit engineering plans and specifications for new water systems or for improvements to existing systems to ensure that each system is capable of meeting safe drinking water standards. The plans must be reviewed before construction can begin. TCEQ completed compliance reviews of 2,477 engineering plans for PWSs in fiscal 2021 and 2,517 in fiscal 2022.

ENFORCING COMPLIANCE

EPA developed the Enforcement Response Policy and the Enforcement Targeting Tool for violations under the Safe Drinking Water Act. TCEQ uses this tool to identify PWSs with health-based or repeated violations and show a history of violations of multiple rules. This strategy brings the systems with the most significant violations to the top of the list for enforcement action, with the goal of returning those systems to compliance as quickly as possible.

Additionally, any PWS that fails to have its water tested or reports test results incorrectly faces a monitoring or reporting violation. When a PWS has significant or repeated violations of state regulations, the case is referred to TCEQ’s enforcement program.

More than 98.8% of the state’s population is served by a PWS producing water that is in compliance with the National Primary Drinking Water Standards.

REVIEWING WATER DISTRICT APPLICATIONS

The agency reviews applications to create generallaw water districts and reviews bond applications for water districts to fund water, sewer, and drainage projects. The agency reviewed 574 water-district applications in fiscal 2021 and 595 in fiscal 2022.

Ensuring Adequate Drinking Water Supply

EXPLORING NEW SUPPLIES THROUGH ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT

The population of Texas is expected to reach almost 46 million by the year 2060. Planning well in advance is critical to sustaining increasing water needs in a state that experiences prolonged droughts, floods, and other challenges. Recognizing this, more and more public water systems are beginning to propose the use of less-conventional sources of water that often require complex innovative treatment.

TCEQ’s engineers and scientists use their expertise to help guide public water systems in selecting effective innovative treatment technologies, and to ultimately grant approvals for those technologies while ensuring that the treated water is safe for human consumption. Some examples of challenging water sources that require such technologies are groundwater with elevated levels of nitrates, radionuclides, or other contaminants; saline or brackish groundwater; seawater; and effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants reclaimed for direct potable reuse.

DISASTER PREPAREDNESS

TCEQ’s disaster preparedness program assists public water systems and affected utilities in providing a safe, adequate, and continuous supply of drinking water to their customers before, during, and after a disaster by using an all-hazards approach. Affected utilities across the state are required to implement a TCEQ-approved emergency preparedness plan that lays out how they will provide drinking water to customers during an extended power outage.